In the 1930’s, the world was enthralled by the burgeoning world of science fiction – a genre that slowly shaped up throughout the 19th century. Sci-fi up to that point had been a loose category; often bundled with the more distinct fantasy classification. But as the 20th century rolled, the genre grew in popularity for a number of reasons. One is due to the widespread appreciation of the technological breakthroughs accomplished at the time, particularly in places like the United States. And another, the rise of a platform that allowed the genre to further proliferate: the pulp magazine.

It was there that The Comet—said to be the first-ever known zine–was created.

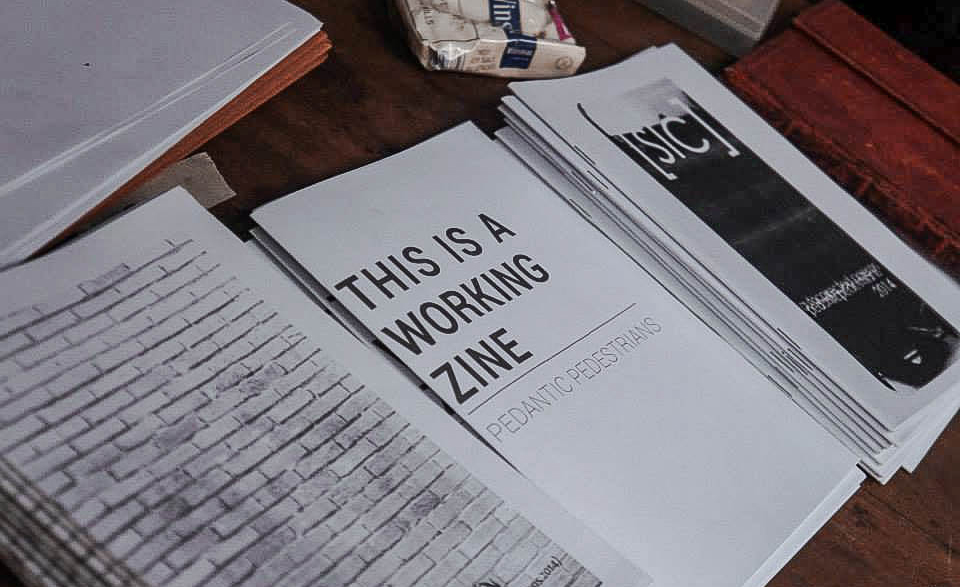

Published by the Science Correspondence Club, The Comet was a fan-made zine that prominently featured correspondences from sci-fi fans, often talking about relevant issues in the genre and science itself. While there were existing professional magazines dedicated to such topics already, these fanzines held a more intimate nature to them, becoming a platform that went beyond just mere sharing of ideas. It connected the community in ways typical publications could not. This is further enhanced by their low prices and DIY nature of production.

88 years later, the story of how The Comet started still mirrors how the zines of today began. In the local zine scene, it’s essentially these same characteristics that form the backbone of the medium. However, if the sci-fi fandom was what helped push zines into existence, it was the punk community that played a crucial role in its emergence here in the Philippines.

HERALD-X—considered the zine that started it all—was released in 1987 as a way to make themselves known, correct any misconceptions surrounding them, and “articulate their collective frustrations,” as Bernie Bagaman notes in his review of the publication.

But while HERALD-X might have prompted the release of more zines throughout the years, the scene was mostly insular, with micro-communities and sub-groups also having publications that reflected ideas and aesthetics specific to their own sub-cultures. During the time, one might find themselves having to be associated with a particular community–or at least, participating in certain events—to obtain copies of these zines.

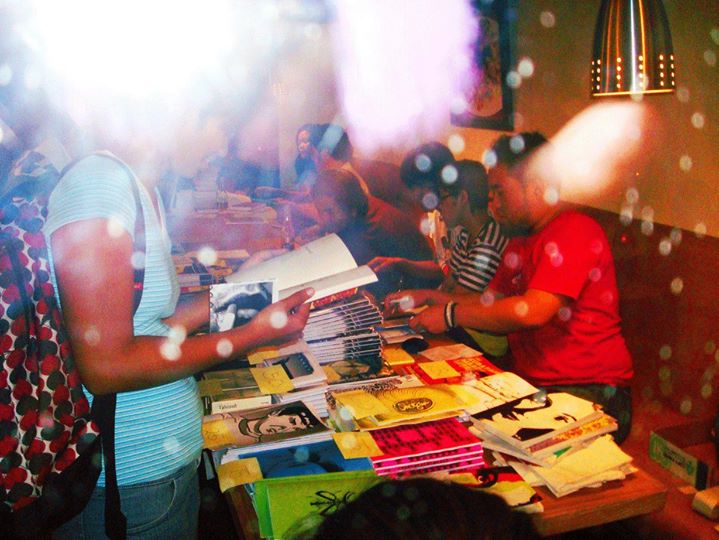

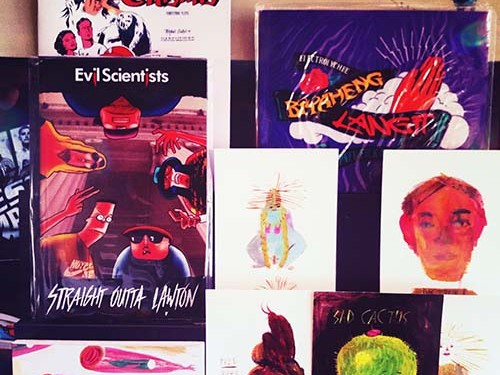

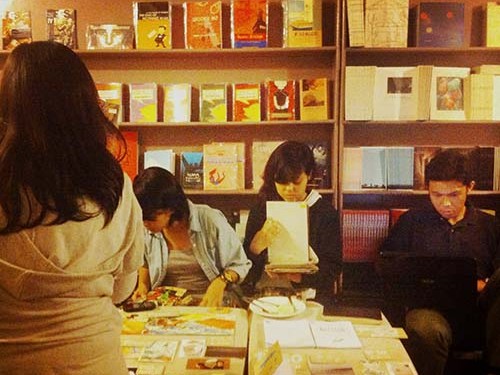

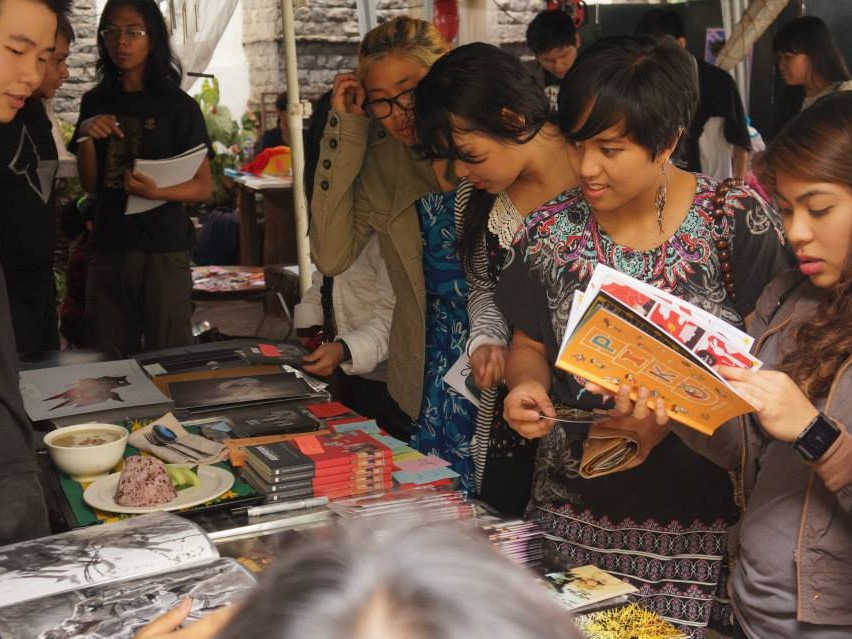

Photos from Adam David of BLTX

For instance, Adam David – co-founder of Better Living Through Xeroxography (BLTX) and a zine veteran—attributes his knowledge of the medium to the Pinoi Punk Community, thanks to his parents Howlin’ Dave and Delilah. He recalls that to get copies of punk-oriented zines, one would attend concerts or go to small stores catering to them, such as the Khumb Mela in Harrison Plaza, Cartimar.

“Historically, zines have been made for mini-communities by people within those mini-communities, typically only relevant to its members,” says David. “So the means of distribution have never been about talking to and convincing people outside of their circle that their mores, aesthetics, or philosophies might be relevant to them.”

In the years that progressed, however, zines began to gain a broader awareness. Part of this, perhaps, could be attributed to the changing technological landscape. When internet proliferated in the 90’s, zinesters utilized it as a way to strengthen their presence. So while zines were still mostly spread via word-of-mouth, the Internet made it easier to follow specific publications.

Paolo Jose Cruz, co-organizer of ZineCon 2001 and also a zine veteran, notes how personal websites–particularly the guestbook function—were a quick, non-intrusive way to get in contact with the zine maker.

“I was a member of international e-mail lists and Yahoo! Groups for zinesters back in the late 90’s,” he shares. “Print or analog zines have always been distributed, at least partly in sync, with digital tech, for as long as I’ve been involved.”

In a sense, the internet served as a way for readers to get updates on specific zines, for creators to share their works further, and for fellow makers to open opportunities for collaboration. Eventually, as the ecosystem shifted gears, so did the zine culture.

“Social media and online commerce platforms made it easier for zine makers to promote and circulate their works,” notes Cruz. But even so, for a portion of the early 2000’s, it mostly remained underground. David speculates it might be because zines often “carried information relevant to the communities they circulated in”—and often, ideas which mainstream culture deems “dangerous or without value.”

What changed, then? One could say that it stems partly from an economic shift, particularly in the creative sector. Cruz notes how in recent times there had been a “general clamor for more tangible analog and print media” as well as a commercial landscape that leans towards “more niche or specialty arts and craft hobbies.” And with this focus on creative work, sprung more avenues. David mentions fine arts classes and workshops about “monetizing art creation,” while Cruz remarks on the emergence of mixed spaces where zines can find a substantial consumer base.

But pinpointing when the exact period zines came into fashion, a lot of it hinges on the growing popularity of fairs, expos, and conventions—particularly Komikon, the largest and longest-running comics convention in the Philippines. Mac Arboleda, the organizer of Zine Orgy and a member of Magpies Press, recalls how his introduction to the scene spurned from joining his college comics organization, where he was “exposed to people who self-published their works, and events like Komikon.” However, he notes that it was WiSiK 2014—an annual arts festival in Los Baños—that he “saw zines that captured the essence of the medium,” and decided to take part in the scene.

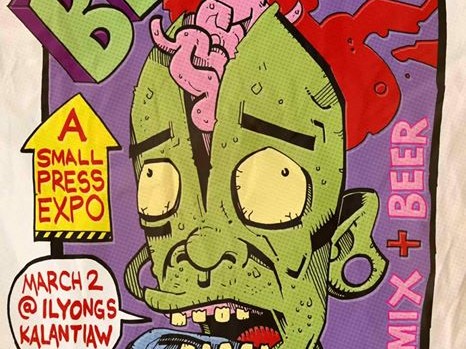

One couldn’t deny Komikon’s impact on the zine landscape. Through a steady combination of marketing and select exhibitors, zine creators were pushed into broader public consciousness and propelled the scene towards popularity. But while the convention might have shed more light on the platform, its spread was heightened by the collective effort of various communities and movements around the country, like BLTX and Magpies.

David, for instance, notes how Komikon and BLTX showed different sides to the community: while Komikon showed the fun in creating such publications and the value of the medium, expos like BLTX, on the other hand, had reminded audiences that zines are part of a “small press tradition” that is meant to challenge status quo ways of thinking and judgment. And there’s Arboleda who remarks on the growing number of art collectives and events dedicated to the craft beyond the Metro Manila area, such as Zine Orgy and Elbikon.

But with zine culture’s growing prominence, there are bound to be some snags. David notes, for instance, the “mercenary attitudes” that may arise with some creators, such as selling zines at exorbitant prices and limited print runs despite their origins. Fortunately, despite its surge in popularity, the spirit of what zines were meant to be continues to live on, even onto newer generations.

Arboleda, who has been in the scene for three years, notes that he was initially attracted to zine creation due to the “appeal of being able to ‘publish’ your work on your own.” Nowadays, he finds that most of the attraction comes from a “re-evaluation of the importance of print,” particularly in this age of fake news and revisionism. But most importantly, he notes how their allure comes from how accessible they are, with their ability to tap into raw emotions and form communities—a feat that zines continue to do more than 80 years later.