Lope Navo was on his way to Rio de Janeiro when he got in touch with us, and as a ‘citizen of the Earth’—an adjective he so fondly uses to refer to himself—this kind of encounter was not strange to him. He has lived in at least four different continents, more than seven cities, and has been capturing scenes all around the globe beginning at a young age. This extraordinary foundation gave him a unique perspective, and it was most apparent when his photography found its way back to his home—Manila.

“Manila is a very interesting city,” he shared. He proceeded to quote Jessica Hagedorn in her work Dogeaters to describe the urban jungle he once called home, “We Pinoys suffer collectively from a cultural inferiority complex. We are doomed by our need for assimilation into the West and our own curious fatalism.”

In his series, he pointed out this brand of identity of the capital city, or to be more specific, his perceived lack thereof. He sees Manila as a city of people descending from warring tribes, indoctrinated by two countries with fire and fury, only to be reunited by the thirst for her own Hollywood dream. It was a city of layers, made up of Western capitalism and European piety, built on self-inflicted poverty where her flashy city lights can never reach.

It is a city painted with her own identity crisis—a struggle to reconcile her own extremes, like a child owning a reflection that is not her own. “There’s no other city in the world like Manila, since we can’t say it is Chinese or Spanish,” he says. “Can we still say it is Malay or indigenous? Can we say it is American? Or European? What is the Filipino identity? Are Filipinos ‘white-skinned’, since all the gamut of billboards and celebrities on its TV tell us so?” These are just some of the pressing questions that come up when looking at Manila from this point-of-view.

When Lope first came back, he was stunned at how Manila changed in a lot of ways. New shopping malls, parking spaces, and condominiums were built on top of the same things that also once promised progress only to be discarded just the same when they have outlived the society’s impulsiveness. Yet even with those extreme changes, Manila still cannot find its place. Not even in the way Filipinos capture her essence.

“The city itself is almost like an airport or bus terminal, it is like a futuristic dystopian film, I felt really estranged from it,” Lope shared. “But one of the most heartbreaking thing is that I can’t pinpoint what FIlipino art or photography is. What do they do that is distinctly theirs? Most Filipino painters and photographers are mere regurgitations of what is popular in the West, there is no real voice, it is all mimicry.”

To Navo, Manila is a juxtaposition of societies, a product of chronic imperialism where people grew comfortable with. To him, it was not as different as Rio de Janeiro, a third world country that was also a product of long years of colonization. But even with the colonizers long gone, the conditions relatively remained the same. Filipinos are still bound by lack of opportunities, daily struggles of putting food on the table, and by traditions that, once upon a time, demanded their subservience.

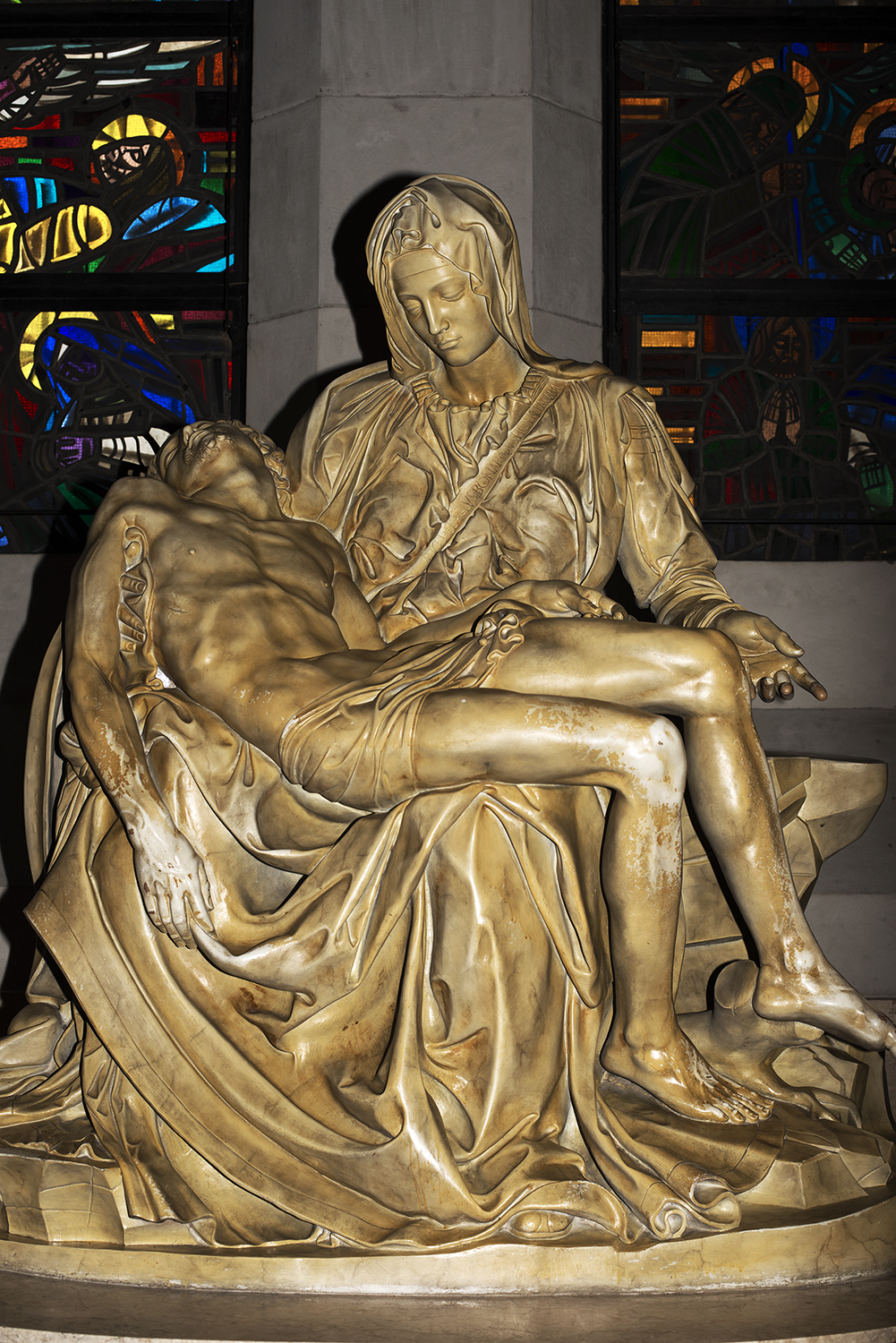

He said, the real identity comes from these people and the places they frequent: wet markets, narrow alleyways, over-crowded street slums, and churches. These places, despite being crowded, noisy, and dirty, serves as the beating heart of the society. Lived in by those who relied on faith to escape the claws of poverty.

“One of my favorite Filipino movie is ‘Maynila sa mga Kuko ng Liwanag’ by Lino Brocka. The scenes I shot are mere echoes of this film, the way Manila is like a brokedown palace. So I shot the monuments, the churches, the markets, the places where the real energy of the real Filipinos dwell. I am talking about the real majority who are not sheltered, and are living in extreme poverty, they represent who the real Filipinos are in my opinion.”

In the years of his absence, Lope expressed that Manila has not changed a lot in that sense. Lope Navo frames Manila the way he wanted it to be seen: a city struggling to swim out from the ghosts of her indoctrination. A city still inhabited by a passionate race, lost in the maze of cultures not of their own. A city that hungers for what the world feeds them, instead of what it could feed to the world.

When asked about what photo summarizes his experiences in this series, he said: “I think the photo of the wooden hand of the Nazarene and a Filipino father trying to push his child’s hands to it. It’s like an indoctrination of sorts. It is an endless cycle.”