To write about curiosity is a peculiar thing.

Writing is an expression of curiosity. But, to probe on curiosity’s essence requires an introspection that feels like peeling an onion: the closer you are to the core, the more you want to cry.

Writing my 30,000-word master’s thesis certainly felt this way. I went to university in England, but I conducted my fieldwork in Manila. I was researching how the internet impacted learning in the film industry where I spoke extensively with filmmakers about their creativity. Exploring this interest of mine was thrilling, and, like my many creative projects, the idea of endless possibilities excited me.

Eventually, I was riddled with questions that rapidly compounded one another. Where do we draw the line between acquiring “knowledge” and mindlessly scrolling online? In this process, can we pinpoint the moment we are actually “learning”? My ideas changed as I wrote, and I spliced my chapters until it looked like a word that made no sense. As my deadline approached, I was pushed into madness and became physically, emotionally, and spiritually ill. I dove into a rabbit hole not knowing what was on the other side, shrilling in both delight and terror.

I am a classic example of how curiosity kills the cat, and I believe this excessive inquisitiveness — manifested in the form of imposter syndrome, burnout, and the fear that you are only as good as your last work — is a curse that plagues many creatives.

Yet, despite all that is at stake, pursuing our curiosities is a habit that does not die in vain. There is a reason why cats have nine lives.

The science and culture of curiosity

Research in the field of psychology broadly views curiosity as a desire for information.

Psychologist Daniel Berlyne distinguishes between various types of curiosity. One is associated with surprise or disagreement as we expose ourselves to new sensory information. This is likely why you will show reluctance towards my recommendations for Australian ghettotech, but will secretly play a banger or two behind closed doors.

Me, looking very attentively at an Anselm Kiefer painting at the Copenhagen Contemporary in Denmark.

Another form of curiosity is at the core of what philosopher René Descartes meant by “I think, therefore I am.” Rather than simply searching for new information, ambiguity motivates us to make sense of said information, giving us the satisfaction akin to finishing a project or acquiring a new skill. It is, for this reason, why I take pleasure in knowing that all my years of interest in budots music, the Philippines’ take on ghettotech, brought to fruition a virtual music party inspired by the sound, which I co-organised. Not only did it demystify a part of culture lacking explanation, but it brought me closer to people who shared this same peculiar interest.

There is a type of curiosity teetering the fine line between acquiring rich versus useless information — one that refers to the unspecific search for the new, such as during boredom. This is why I procrastinate by impulsively pulling to refresh, checking my notifications, or watching YouTube videos — from quantum mechanics to chickens wearing pants — as I foolishly attempt to finish this article.

Knowledge is power

Curiosity motivates us to learn. But what is the thing we are learning, and for what purpose?

To explain this, we need to establish the difference between information and knowledge. Information is something conveyed by a particular “sequence of things,” whereas knowledge is the sum of what is acquired through experience — “the theoretical or practical understanding of a subject.” When we internalise information following that initial curiosity, we tailor the information to our intellect (i.e. learning), effectively becoming knowledge.

Knowledge is the secret sauce to all things creative, of which there are two types. Explicit knowledge consists of easily replicable and readily accessible information. In my fieldwork on the learning capabilities of filmmakers, many referred to films as an invaluable source of inspiration — a form of explicit knowledge.

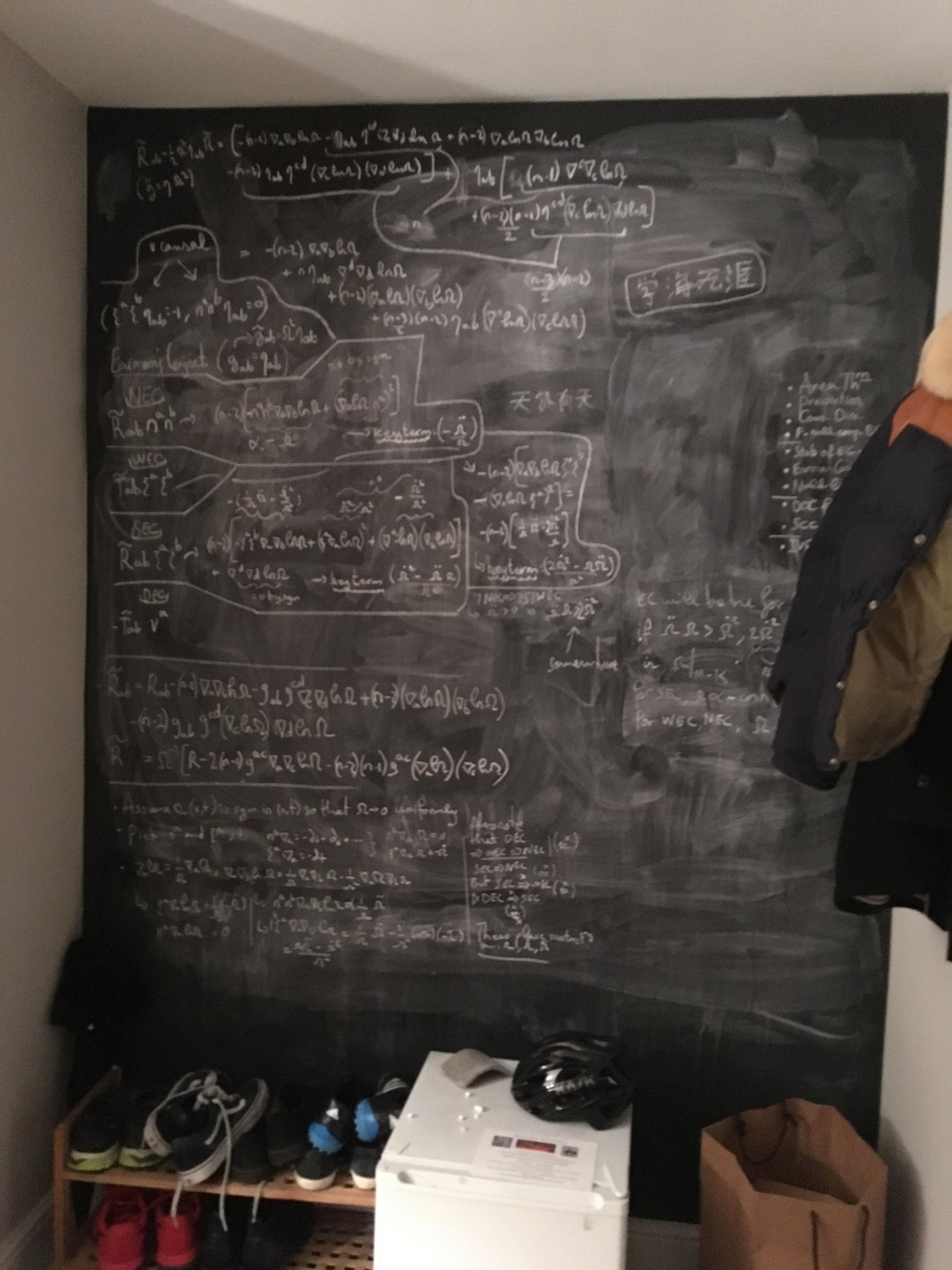

This is a photo I took of my friend’s blackboard after a dinner party at his house. He was doing a PhD in Philosophy and his research interests included theoretical physics, general relativity, and space-time. This blackboard was one of the many delightful curiosities I encountered during my master’s degree. My friend is now a fellow at the Black Hole Initiative at Harvard University.

Preceding explicit knowledge and co-existing with it, tacit knowledge is not easily expressed or measured, being those things we know more of than we can explain. In his book Tacit Dimension, philosopher Michael Polyani describes holding such knowledge as “an act deeply committed to the conviction that there is something there to be discovered. It is personal, in the sense of involving the personality of him who holds it, and also in the sense of being, as a rule.”

For me, tacit knowledge is realised after it is used unwittingly. If you asked me in 2012 whether I will write this article in eight years — being 17 years old, on Blogspot, aspiring to be Miranda Priestly — I’d tell you I would rather be caught dead wearing florals during spring. Yet, the fact I am still “blogging” shows how bygones do not just become bygones; they live in the interiors of our minds as drapes and chandeliers, ready to impress when you decide to enter it.

Either that, or they live on the internet. Forever. And ever.

The cat killed itself

Curiosity can cripple its subjects as thoughts spiral into infinity.

In the late 19th century, poet Paul Verlaine coined the term poète maudit (or accursed poet) to describe his fellow poets — ostracised, self-destructive, and in contempt towards their art and life. The Buddhist concept of taṇhā is relevant here, referring to those intense cravings that can cause catastrophic thinking in the face of deprivation.

My cat, Kuro, looking unamused.

There is something to be said about curiosity as a reflection of our addiction to thinking. The hijacking of the term “curiosity,” in advertising and technology, shrunk its meaning to either a survival instinct or an impulse — a thirst for information, to have a “competitive advantage.” The experience of curiosity is pure, being closely connected to childhood. Yet, for many creatives, it is simply instrumental or what artist and writer Jenny Odell described in her book How to Do Nothing as “seeing things or people one-dimensionally as the products of their functions.”

As someone who feels like a potato with every day spent not writing, I struggle giving advice for kicking this mentality. But, when I am not over my head, I find comfort knowing that the world operates on probabilities and there is an enjoyment that awaits in this creative project called life.

For the sake of it

Having said that, curiosity is best enjoyed when done for its own sake and ownership of this enjoyment needs reclaiming.

When I am asked about my hobbies, the first thing I usually say is writing. This always catches me off guard because it is partially true. The word hobby is a shorthand for “hobbyhorse,” a toy horse, denoting an “activity done for pleasure.” Yes, writing is all these things for me — it helps purge my thoughts — but it is something I agonise over too. Growing up, I was told I should do what I love and I’ll never have to work a day in my life. Adam J. Kurtz, author of Things Are What You Make of Them, reiterates this phrase to feel more relatable: “Do what you love and you’ll work super fucking hard all the time with no separation or any boundaries and also take everything extremely personally.”

A tropical quarantine curiosity: A palm tree sticking out of someone’s roof.

As creatives, to achieve creativity, we are conditioned to commodify our curiosity. While I frequently thrive in this agony, I am trying to dial back from such extremes by renegotiating my understanding of “leisure.” Josef Pieper, in his book Leisure: The Basis of Culture, believes leisure is “necessary preparation for accepting reality.” It is an existential condition and cannot be enjoyed if it is simply thought of as a “break from work” — a symptom from our culture of “compulsive workaholism.” Leisure, he asserts, operates in direct opposition to work, being concerned with restoration and effortlessness. He sums it up here perfectly:

Leisure is not justified in making the functionary as “trouble-free” in operation as possible, with minimum “downtime,” but rather in keeping the functionary human … and this means that the human being does not disappear into the parceled-out world of his limited work-a-day function, but instead remains capable of taking in the world as a whole, and thereby to realize himself as a being who is oriented toward the whole of existence.

By pursuing this spirit of leisure, not only are we reclaiming lost time to relish in curiosities that add richness to our lives; in doing so, it brings dignity to our hopes, aspirations, and well-being.

As I write this last sentence, I look forward to returning to unburdened contemplation. Only after then can I use one of my nine other lives.

This piece is an exclusive collaboration with Cultural Learnings. Cultural Learnings is a newsletter on contemporary culture, written by journalist Sai Villafuerte. You can follow Sai’s work by subscribing to Cultural Learnings or following her on Instagram.