Before August 2018, the whole world didn’t know who Greta Thunberg was. She was just a 15-year-old girl who wore a bright yellow coat while holding a sign outside of the Swedish parliament that translated to ‘School Strike For Climate.

In the following weeks after that, the single protester in her was no longer alone, but this is not to say she ever was. She was joined by other students and together, they demanded accountability from world leaders, campaigning for more action against climate change.

At each strike, they continuously called upon the youth to join in their school walkouts every Friday. In less than a year, one single act from a teen turned into a global movement called #FridaysForFuture with about 3.6 million youth climate strikers across 169 countries.

The youth of today no longer want to glaze over climate issues that were passed down by the generations before us. Everywhere in the world, at least one child is fighting against these failures.

In the Philippines, one of the co-founders of the country’s #FridaysForFuture chapter, Youth Advocates for Climate Action Philippines (YACAP), is Mitzi Jonelle Tan. Before becoming a youth climate activist, Mitzi was a university student taking up BS Mathematics. As a member of the organization, Agham Youth, she has always had a strong belief in the development and use of science for the benefit of all people.

Over a zoom call, we talked about climate justice, the youth’s role in the fight for our future, and why it’s so hard to be an environmentalist in the Philippines.

What are the visions and goals of your organization?

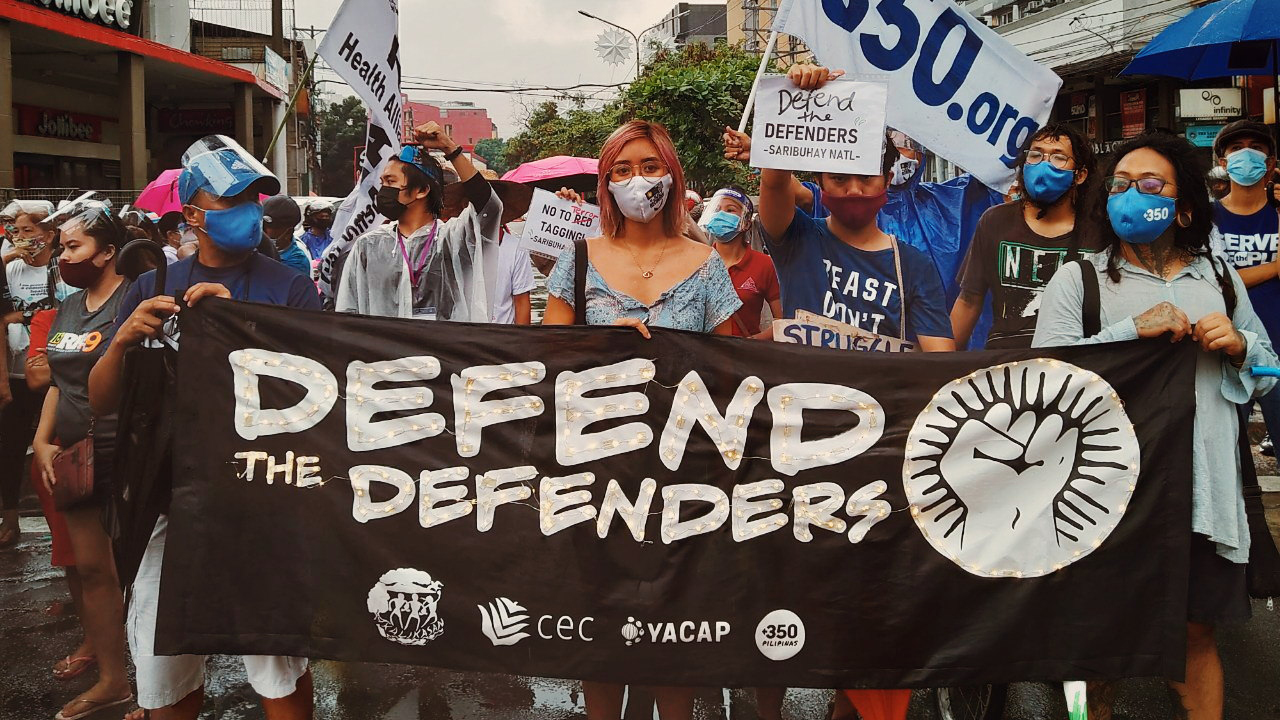

YACAP has 5 points of unity: climate justice, the urgency of climate action, defending our environmental leaders, youth-led collective action, and system change. Depending on the year, our campaigns will revolve around either one or more of those points. In one of the climate strikes before, the theme was ‘Defend Environmental Defenders.’

Raising awareness in the Philippines was one of the biggest goals for the longest time of YACAP, especially when we just started. Even if we are familiar with climate change and its impact, a lot of people are not familiar with the science behind the climate crisis—that it is actually man-made. It is something that shouldn’t be natural. Climate change is natural. The Earth really will warm eventually, but the current rate that it is warming isn’t.

That’s something that people don’t know so a lot of them feel powerless against it. To them, it seems as if their enemies are natural disasters. We have to remind them that there is something that can and should be done and show the intersections of climate issues with social issues because the ones that are most impacted by the climate crisis are usually the ones who are also experiencing other social and economic issues.

Photographer — Zaldine Jae Alvaro

How do you deal with the difficulty of raising awareness about the climate crisis when we as a developing country have so many other issues as you mentioned?

It depends on who we are talking to. When we talk about the climate crisis, we make sure to customize or contextualize. Before the pandemic, we would go to the farmers when they would pay a visit at the Department of Agriculture. If it’s farmers we’re talking to, we wouldn’t talk about sea levels rising. We would talk about droughts and strong typhoons. We ask them what they’re seeing and experiencing, and we learn from their experiences. We would then tell them about the climate crisis and the reason why what they experience is happening.

If we’re talking to fishing communities, which is what we used to do a lot more during the lockdowns, we talked about the sea levels rising, their experiences of the mangroves being cut down, and its impact. It’s really more of an exchange of education—them to us, us to them. It really depends on who we’re talking to; we change the way we approach the issue.

Our most recent community teaching was with the Marikina mothers. A month after the typhoons [last year], they were the ones who approached us first. They had so many questions for us, and the biggest one was, “What can we do?” They wanted to learn because they wanted to know what they could do to stop it. I feel like that’s what’s most important about climate education—empowering them to do something.

What for you is the role of the youth in environmental activism?

It’s so important that the youth are leading the climate movement because we’ll be the ones who will—as cheesy as it sounds—inherit the earth. We are the ones who will experience the worst of the climate impacts because if everything goes on as it is happening now, the climate crisis will only get worse and we’ll be the ones who will live through that extreme warming of the planet. This is the generation that must change things because for the next generations it may be too late.

At this point, we need everyone to join us. Everyone has a role, and everyone is needed as long as you have the intention to care. Activism for me is all about decentering yourself and centering the people that are most marginalized and amplifying their voices, making sure that in everything we do, we have them with us. Otherwise, the people who have been fighting the hardest and the longest will be left behind when we develop.

There are many different areas of climate solutions in development. Which is most immediate?

One is climate education. For climate education to work, you have to make sure that education itself is accessible to everyone. A dream that YACAP has had since we started is to have climate resources or even just a climate 101 dictionary in different dialects in the Philippines. That’s something we’re trying to work on, but it’s just so hard because we can’t even translate some terms in Filipino. Carbon dioxide emissions—how do you even translate that? And it just echoes the fact that education in the scientific community is structurally biased to the people who can speak English. We’ve been talking to a lot of people about this so it’s a work in progress.

Another is climate risk management. I think we should be developing our plumbing systems and warning systems because of the worsening climate so that we can adapt properly. We don’t even have proper evacuation centers. People would go to evacuation centers, but the centers would also be flooded because they aren’t made to be evacuation centers in the first place; they’re gyms, churches, and schools. We should be developing our infrastructure, knowing that all this is happening already. It’s not even preparing for the future because it’s already our present. It’s all happening today. Marikina now has alarms because of the Ondoy flooding, but it isn’t enough. Sure, it alarms and people do evacuate, but where do they go?

Images from YACAP

Sustainability now has become so popular that it’s becoming more of a trend. What do you think of that?

For me, I don’t mind that sustainability is becoming more trendy because that means more people will be interested to join, but I think the role of the activists is to make sure it doesn’t stay at the corporate level of sustainability that’s being advertised so much. It’s not even true sustainability sometimes, but green marketing. It’s good that people are starting to think about how what we’re doing might be small things but are impacting the environment. What we must be careful about is that a lot of the sustainability propaganda that we see on mainstream media or social media are being pushed by corporations that are causing most of the climate crisis.

The term carbon footprint was developed by the fossil fuel industry. It’s fine because when you call for system change, it’s hypocritical when you don’t do personal lifestyle changes, but of course, there are different levels of privileges for that. I don’t mind if you start with individual actions but remember to hold big corporations accountable too.

Even the way we approach plastic pollution is always about reuse, reduce, recycle, but when you segregate at home, it all gets dumped in the same place: in the landfill, which has no segregation. When we talk about plastics, it’s not a separate issue from the climate crisis and the fossil fuel industry. As we push fossil fuels out of the energy sector, we might see that they shift into the packaging sector, so we have to be careful about that as well. They all go together.

What do you think are the challenges in achieving climate justice when there are so many key factors and stakeholders needed to put together and get on board?

Awareness is such a big thing. I’ve seen changes in how the media portrays typhoons and climate so there has been an improvement. There have been some changes in how we talk about things. That’s why we don’t even have ‘climate justice’ in our name in YACAP because if I weren’t a climate activist, and you told me that term before it was even popularized, I would not know what you mean by that. Is that weather justice? What does that mean? It’s such a floating concept so it becomes a big challenge because before you can talk about anything else in detail, you must start from scratch.

The people who started YACAP in 2017, all got into this after speaking to indigenous leaders or the lumads in UP. That’s when we realized that we have to do something, so we actively got into learning more about the environment and the climate crisis. We know not everyone has the chance or time to dive into all the science which is why it’s good that there are so many organizations now raising awareness about it.

Another challenge is how activism is taboo here in the Philippines, especially if you’re young. I work for Fridays For Future International, and a lot of them are so much younger than me because in other countries, it’s normal to get into activism at 14, but here, that’s not the case at all.

The stigma is connected to how dangerous it is here in the Philippines. A lot of what we want to do is show that it’s fun, creative, and engaging so they see that it’s not scary to be an activist. If we want people to join us, we must be approachable and welcoming, and that’s one of the good things about YACAP because we all know that we need everyone.

Conservation and sustainability have long been practices but it’s becoming more relevant, especially with climate change and how it’s affecting our communities. What do you think were the pitfalls of the previous government and even environment leaders and how do you manage to overcome those and be different?

In the past 12 years, ever since Global Witness started counting the deaths of environmental defenders across the globe, we’ve always been in the top five. That in itself is a huge pitfall already. Why is activism so dangerous in our country, especially for environmental activists, at a time when the environmental crisis is so widely experienced in the Philippines? When you are experiencing the worst of typhoons every year, you would expect that they [the government] would listen to the people who are protecting the environment and trust that they would know what they are doing. Instead of listening to them and protecting them, they are the ones being harassed, displaced, and killed.

As for environmental leaders, I feel like I’ve only been talking to a part of all environmental leaders so that is a pitfall too—that we’re not a more connected community. The plastic waste activists for example or the climate activists and the conservationists, all have their tenets. It’s good that we all have our focus points, but we really should be working together more.

There’s a lot to do together. If Fridays For Future can have communications across the globe in every continent, I’m sure that’s something we can do here: build a network or have a space where we can talk, especially when we’re in the same country.

What do you have to say to the youth? Those that share your activism and those who don’t?

Don’t be afraid to ask questions. Don’t be afraid to reach out to people because it starts there. It starts with knowing what you want to talk about. I became an activist first before knowing. It’s okay if you don’t know everything. We don’t need one perfect activist, there will never be a perfect activist. We need a billion imperfect activists because that is so much stronger.

When you feel alone, you have to remember that you are not alone in this. We are only joining others like our indigenous people who have been fighting for this for so long. We’re also everywhere. There is someone on every continent fighting for climate justice. If you aren’t an activist yet, join us because we need you. There is a role and place for everyone, even if it feels so scary.

The youth want more commitment to climate solutions that include concrete plans, clear strategies, and contributions that will make a difference. They don’t want awards or magazine covers. They want to focus on schools. They want to actually be heard by the adults who are supposedly leading the way. More and more, we see other kids bringing a seat at the global family table.