In the greater world of art and illustration, an important point that every artist comes to terms is knowing how to toe the line between evocative visuals and a striking message. Though political cartoons and politically-charged editorial art have been present in the local and international spaces, its prevalence considering recent events is an understated one. 2020 has much credit to its content, after all. Knowing this, Marx Fidel got to share with us some words about art and the greater body of illustrative activism in his life.

Art brings a message, and with it, the ability to carry sentiments through. From the lowliest creator to the highest platform, we spoke about the ways that political cartoons can have a role in carrying meaning and comfort through times of tyranny.

What inspired you to start political commentary through art and illustration?

I used to do small projects here and there before 2020. It was only last year that things started to ramp up. I worked at We The Pvblic at the start of the pandemic, and it was also around that time that various local issues were starting to worsen. It was then that they tapped me for something more topical for my art. It just so happened that what I did would soon go viral. Since then, I’ve been doing similar things with my art.

The first illustration that went viral was about the slow response of the government during the start of the epidemic. The fact that people were so bottled up—especially with the backlash towards Koko Pimentel’s action—led to a boiling point. Ultimately, it was because of his privileged status that he received preferential treatment while other Filipinos were harassed and oppressed. After that, things escalated.

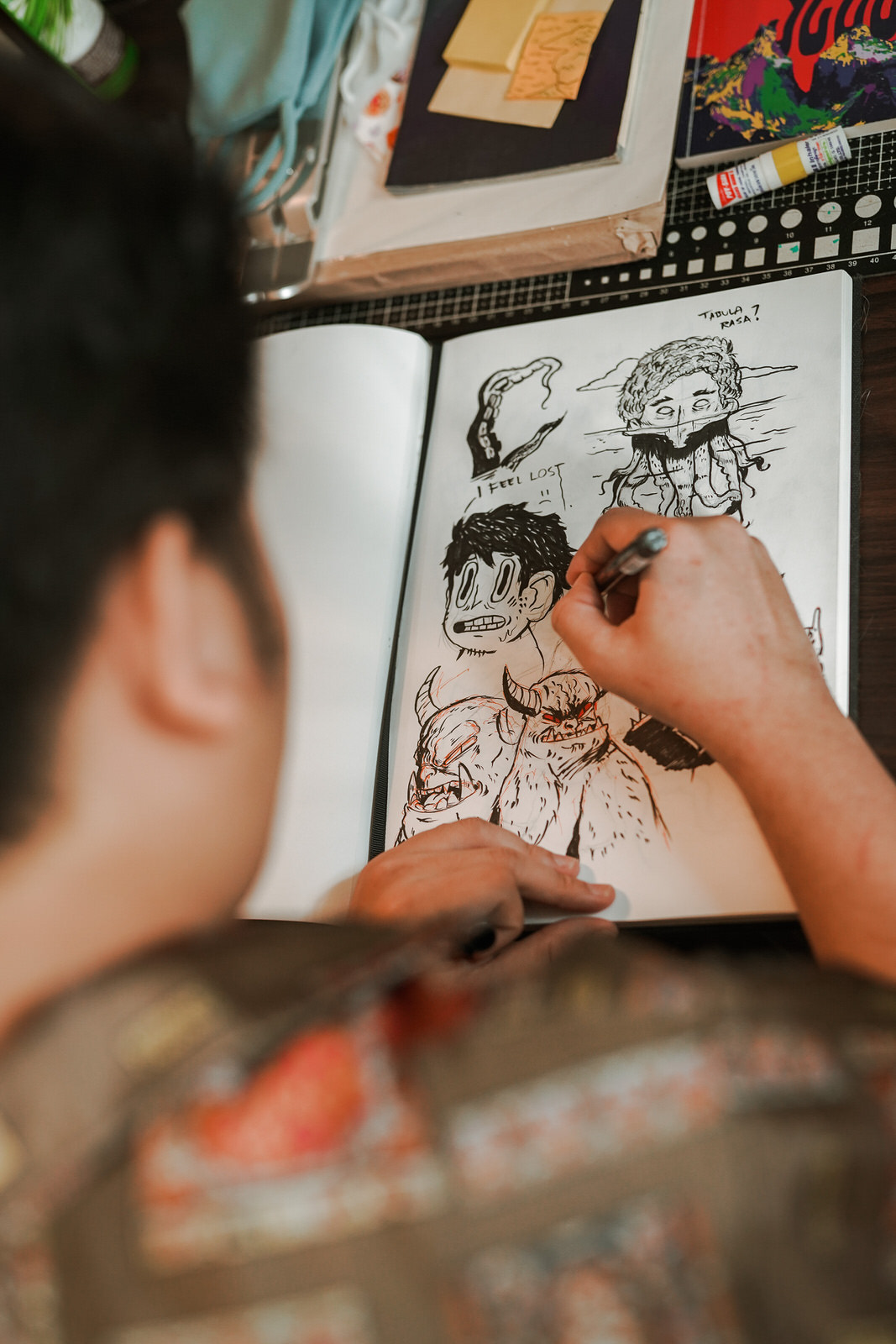

Photographer — Zaldine Jae Alvaro

I’m sure it’s come up often – your first name, ‘Marx,’ and the message imparted through your art. Is there a connection between that and your political beliefs?

I’m left-leaning, though I’d say I’m also an artivist—the activism fueled through art. As for my name, ironically enough, it was my Ninong who was a professor, that suggested it. Since my surname was ‘Fidel,’ and there was ‘Fidel Castro,’ they thought it would be interesting to fix in ‘Karl Max’ somewhere in there.

Funny enough, I only started becoming more socially active and aware in 2016. Before then, I was prone to anti-SJW rhetoric—Ben Shapiro, Steven Crowder, and the like. I know better now. It’s not just about political correctness; it’s about upholding the truth.

Political cartoons have for a long time been associated with newspaper segments. Was there a newspaper you took inspiration the most from?

I got it most from my time in Inquirer. Some unconscious inspirations, sure, but I’d say a lot of my recent influences came from current thoughts over the government and the sociopolitical landscape. Then, it all started to come together.

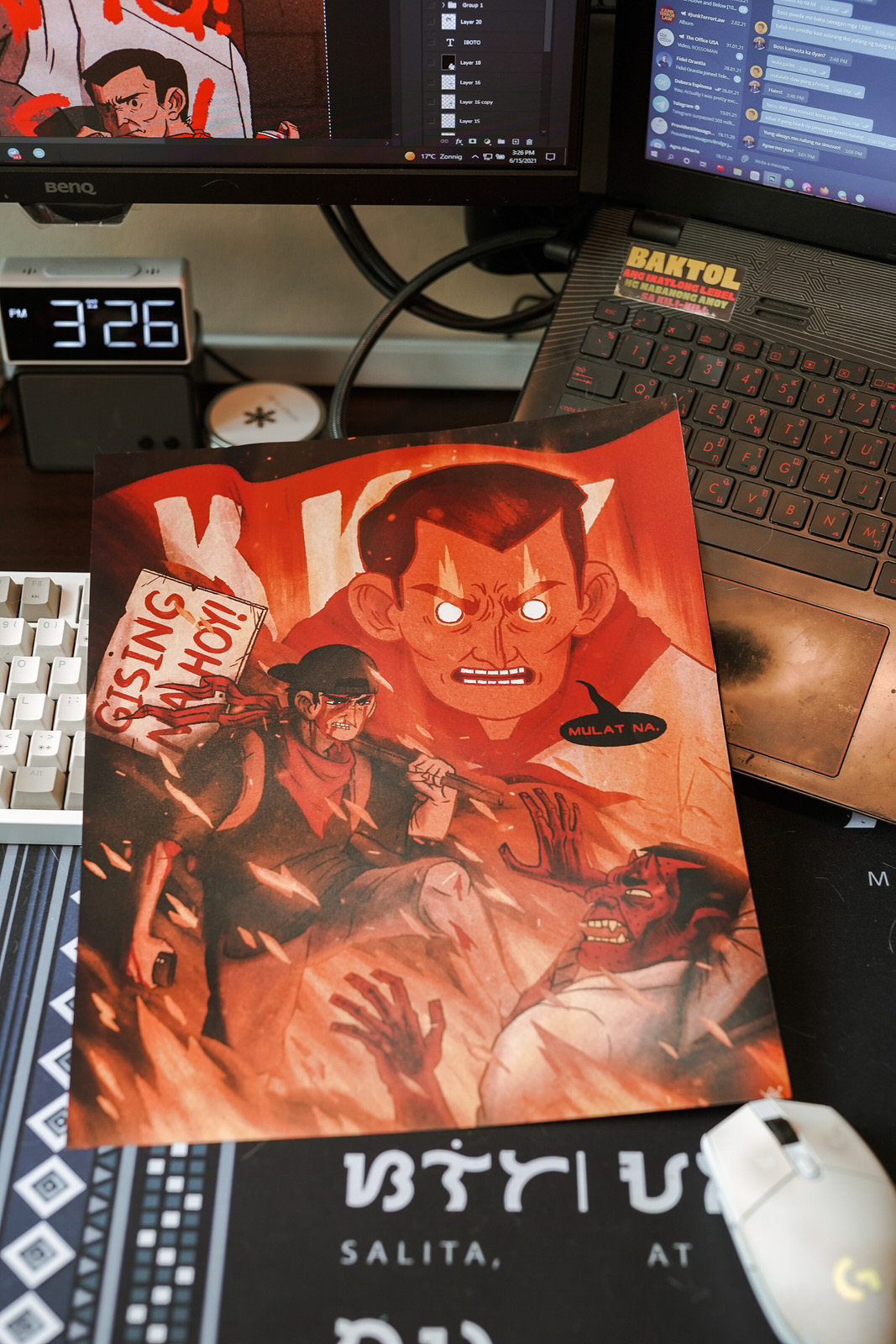

My visual style is attributable to time spent reading and researching Martial Law era political illustrations—very heavy and stylistic. I found out later on that many of the influences from other illustrations I liked took inspiration from those as well like the linear art and compositions. It was after having my own illustrations become more influential and viral that I decided to take a look through at illustrations of the past like the Martial Law illustrations and how they focused and worked on being so prominent. Thanks to the work of scanned archives at libraries, especially online archives, access to these resources was made so much easier.

Why do you think people are so drawn to art that strikes very emphatically with events in the present, i.e. politics?

I can’t say for certain, but I do have an idea.

It’s a humorous take on something serious—even triggering political situations can be absorbed. One of the advantages of doing political cartoons is its entertainment. Not only does it catch their attention, but they also learn more. As opposed to reading articles, some don’t have the time to scour through whole articles or editorials. Usually, the illustration can give you the gist of it.

An artist who does this well, is Tarantadong Kalbo. He condenses all these issues into something that’s understandable, entertaining, but still compelling.

Do you feel as if the political and socioeconomic landscape has changed the way we consume art?

Definitely. Especially in progressing technologies, there’s lots of factors as to why the consumption of media has changed. In social media, fake news is so rampant because of how easy it is to get swept up and caught in it. It’s easy to trust sources or even distrust them because a single fake news article can distract everyone.

Things weren’t as muddied when I was a contributor for Philippine Daily Inquirer, though. While it was sometimes political, my work there wasn’t so aggressive—there were times I’ve had to hold back what I wanted to say.

It takes bravery to say your truth especially in the face of control, censorship, and state threats. How do you maintain a healthy mindset about everything happening around us?

In artistry, it’s easy to become susceptible to burnout, even myself. I started seeking out a psychologist at some point. You can’t fight your fight if you’re unhealthy—mentally, physically, and emotionally. If you’re undergoing some strife, my advice would be to seek help—even simple and small things like speaking to friends, speaking to family. In times like this, especially in isolation, the little things do add up.

How do you feel about mass, or even extreme, censorship? Among most discussions of censorship revolve around fear of who does the censoring or even worse fates.

For lack of a better phrase, delikado (it’s dangerous). I get that everybody wants to just go out there, to come together, and fight. It’s also very easy to feel numb and just say “Wala, eh.” I certainly felt this at some point in time. It felt like each day was just another day of mistreatment from the government, but my friends helped me maintain my conviction. It helped that many of my friends were activists. If they didn’t stop fighting, why should I?

If not in politics, where would you see your art most involved with?

Small-time stuff, maybe. I’ve always liked comics, especially ones with light sociopolitical themes. I really like stories, and even have a few ideas on hand—some fantastical, whimsical, and others fictional stuff –though things in the current landscape have made me shift focus away from i, for a bit. Apocalyptic and world-ending landscapes have always interested me. My all-time favorite series is actually Fallout.

In an age of misinformation and malicious partisanship, it’s hard for most Filipinos to educate themselves against tyranny, especially since class issues aren’t so visible in public forums. If someone wished to educate themselves, where would you suggest they start?

As someone who’s familiar with communities within the lower class, one thing I noticed is they do have the motivation to do things, but the question remains, “Why wouldn’t they work for it?” One of the reasons is the need for survival. They need to eat and work; they can’t afford to split their time between activism and survival. There’s also certain “bubbles.” If you don’t know what’s happening, it’s because of the abundance of fake news around you.

I’m from the middle class, I concede to that privilege, but my friends are more knowledgeable of these issues, so I’m forever grateful. I never had the chance in college to join these socially active groups or organizations so if I could re-do things, I’d start there: recommending they join organizations that involve themselves in the politics of things. Even if I’m not currently unaffiliated, there are groups out there that do help; other artivists, like We the Future PH, if you’re looking to involve yourself.

There is very strong imagery in your cartoons about the stalwart fighter, the warrior for freedom. With that in mind, did you have a favorite among the heroes of the Philippine Revolutionary War?

It’s a bit cliché, but I’ll admit to having a great respect for Andres Bonifacio. It was his way of urging people to move and do something, that moved me. As an educator, illustrator, or cartoonist, I’m trying to push people to do something or inform them with my illustrations. Even if you’re not perfect, you still have to move people.

You use your cartoons to paint a light in the dark, and to light a path for others, enraged and sympathetic. For those not as talented, who can only consume art, how would you inspire hope?

It is, I’d imagine, hard to be hopeful. I used to have ex-DDS friends and they’d ask me what one could do to make up for the harm of their beliefs. There’s even a group based around those who’ve reformed ‘Kwentong DDS’ for those trying to rag themselves out; it’s a super funny group.

Be vocal. Beyond that, you must show and make an example of your change.

Getting people to look at you and wonder, “Why did you change?” or “What happened?” or “Why did you change your mind?” about your sociopolitical leanings. That’s what it’s about. When people ask these questions, the seed of doubt in their mind can lead to better questions, research, own introspection—it’s a domino effect. For something as straightforward as just asking yourself a simple question can lead to showing the world, and yourself, that you’ve changed. It serves as an inspiration for others to change in their own ways too.

Be vocal.