Around this time last year, Manila was on the precipice of what would be known as the world’s longest lockdown. The most dreadful scene? Walking down the aisles of the grocery store, seeing nothing else but empty shelves save for a few items. One thing was obvious: people were scared of going hungry.

It was apparent that COVID-19 has disrupted the supply chain due to several reasons like food demand and consumption, movement restrictions, slower production due to a skeletal workforce capacity, and limited logistic infrastructure.

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization in their 2020 report, at least 18.8 million Filipinos went hungry even before the onset of the global pandemic. As an agricultural and maritime country, it is a tragic irony that the Philippines battles problems of food insecurity. Farmers and fisherfolk who produce our food are among those that struggle to eat the most as members of the poorest sectors of our society.

Aside from being prone to natural disasters like typhoons, floods, droughts—all of which have increased in severity because of climate change—many other factors, including government policies, lack of mechanization, and inadequate support for research and development contribute to the Philippines’ flawed food system.

It remains unhealthy with the domination of a few food commodities; unjust as the pricing burden is carried by producers and consumers, while traders get most of the control; and unsustainable due to industrial food systems’ continuous contamination of soil and water resources.

Currently, urban populations tend to disassociate the connection between consumers and producers, lacking awareness in issues that involve food production and the environmental implications of what we eat. So, how exactly are we supposed to successfully strengthen the relationship between cities and nature to close the gaps in the supply chain and transform our agriculture’s current model?

As our population grows and the demand for access to safe and sufficient food increases, an emerging agricultural revolution could just be one of the many ways we can keep the nation fed efficiently.

We spoke with two indoor vertical farm founders, Ralph Becker of Urban Greens and Derya Tanghe of Future Fresh to discuss Philippine agriculture, sustainable cities, the urbanization of food, and what it is like to run an agritech business.

Both brands have designed and built their own indoor farm systems that make use of hydroponics as the method of growing their crops, which means that they do not work with soil as their growing medium in the process. Instead, the nutrients usually found in soil, which plants need to grow like potassium, magnesium, and calcium among others are mixed in water.

Ralph Becker, Urban Greens

Ralph is the CEO and Founder of Urban Greens, which he started in 2016. Before coming to the Philippines, he worked in business development for a tech company, trying out their latest technologies and working together with different stakeholders.

“Hydroponics is not something new. The ancient Greeks and even the Aztecs were known for using it. It was also believed by archeologists that the hidden gardens of Babylon; the reason why they were able to grow lush greens in the middle of the desert was based on hydroponic knowledge,” he explained. Hydroponics involves growing produce with as simple as a jar, net pot, foam, nutrient solutions, and water.

When asked why he started Urban Greens, he said that he discovered a lot of the vegetables and herbs in the country are more expensive than in most places in the world. They are also not as good, which could only mean that they don’t have as much nutritional value because produce usually loses some of its nutrients days after harvest.

“They’re very difficult to grow here. That’s another reason why we import them a lot from China, Australia, New Zealand, Vietnam, Thailand, the US, and Europe. I find that shocking for something that doesn’t have a long shelf life. Sometimes, even if you keep your veggies in the fridge for a couple of days, they still go bad, so that means that they’re not as fresh as they were when they were harvested because of all the time they took in transport.

According to Ralph, however, hydroponics is only one aspect of Urban Greens’ methods. “Hydroponics is a means to an end, but it’s more the indoor aspect that makes a difference. [When] indoors, they’re protected from typhoons, droughts, and the change in seasons. It’s the same principle as you and me. You sit inside your condo or your room and even if it were hot or humid outside, you hardly care because you’re indoors. If it were hot, you can turn on the air-conditioning. If it were dark, you could turn on the light. Here, you can control your environment and that makes you a happier and more productive person. We’re basically making plants happier and more productive by protecting them from anything that can affect them, just by putting them indoors. We then use the method of hydroponics to maximize the indoor space and to give them the right supply of nutrients they need to maximize their potential.”

As someone who loves food and learned about cooking from living in different countries and even working for a time as an assistant chef in France, Ralph is more particular about the quality and taste of food. “I have a very strong relationship with food and pay attention to food. Now that I’m more involved in the food industry, I’m more aware of how food is grown and it’s not always in the best, cleanest, safest, or most eco-friendly conditions. It’s important to have a balanced diet and to be more mindful about where your food comes from,” he says.

The state of Philippine agriculture has not been at its best in years and is facing a lot of difficulties. With the average age of the Filipino farmer being 64, most of the younger generation no longer want to work in the fields for very low wages, which may pose huge problems soon.

“I’m not saying that what we do will be the solution to everything. We can’t grow some crops like corn for example. We only produce a fraction of all the food that we need. But at least we provide an efficient, sustainable, and advanced solution. We use 21st-century technology that we developed in-house. It doesn’t come from anywhere else. Our engineers built it. I built it. This is made here in the Philippines by us and we’re really proud of that,” admits Ralph.

Before the pandemic, Urban Greens operated by crowdsourcing vacant commercial and residential spaces. You would find them in parking lots, rooftops, and basements. However, they’ve recently taken the time to change the way they operate and have just moved into a warehouse in Makati. With a bigger facility, they will be growing about 40 crops of leafy greens, herbs, and fruits.

“The major cities around the world are adapting, putting up urban farms in the outskirts of the city or in the city itself. It’s a growing trend and this is something that will be more impactful moving forward. It’s here to stay and will become an important part of the urban landscape in the years to come.”

Derya Tanghe, Future Fresh

Before Future Fresh, which has been operating for over 2 years, Chief Marketing Officer and Co-Founder Derya Tanghe built an ed-tech school called NXTLVL academy to focus on training multi-faceted tech education. With his interest in the field of tech and innovation, he’s always wanted to bring in new technology in different industries and agriculture is one of them.

When Derya and his team first started the business, they spoke to restaurant owners and other purchasers and were astounded by the amount of food waste. He said that consumers were mostly frustrated because the produce starts wilting in a day or two and so much of what arrives needs to be sorted for quality control.

“On average, produce travels more than 300 kilometers from farms to the end customers. The distance traveled is a huge factor because generally what they’re harvesting doesn’t actually reach the supermarket or the customer until quite a long way and has traveled a long time. That’s why you see food waste on arrival here being at 50-60% at most. With us at indoor farming, it eliminates all of that. We experience 0 wastage on delivery. For us, the whole goal is to harvest every morning and then deliver to customers right after, so it’s literally as fresh as it can be.”

Food miles are the distance between where food was grown and where it was delivered to be consumed. Food produces more carbon the farther it comes from. This is one of the main issues that urban farms address. By growing food close to the consumers, there are fewer food miles, and the produce arrives in better quality.

We set out to grow the best produce possible, he says: the way we saw to do that was to build controlled indoor environments that allow us to grow, test, and harvest what we see as the finest product that one generally cannot grow consistently year-round. Our focus is on providing top-quality produce that can be available daily. The quality will be at the highest and a consistent level year-round, so there’s no drop in quality and price volatility.

While some people are not convinced with indoor hydroponics as a solution, Derya explains its very nature: “In the basic sense, you don’t need soil. It leads to questions like ‘Is the product going to taste as good?’, ‘Does the product have the same feel or quality?’, and the answer is yes. At the moment our hydroponic and indoor growing systems are essentially 40-foot containers that have been repurposed and re-outfitted to be an indoor farm. That leaves it to be completely indoor and climate-controlled, so that’s why our farm and temperatures are running at around 20 degrees Celsius for a lot of our produce. We focus on non-native plants, so we don’t grow the same as traditional farmers. We look to add versatility and if it is the same crop, there is a definite difference in terms of quality, variety, and taste.”

Other problems that traditional farms face are the lack of end-customer relations and marketing to promote diversity in crops, which could lead to a more resilient and regenerative environment. Since they’re not selling directly to consumers, it’s a lot harder to get information on what the customer needs and there will always be a middleman involved that shares profits. This is where digital technology proves to be very beneficial as it enables a direct connection between farmers and consumers, reducing retail prices and increasing their income.

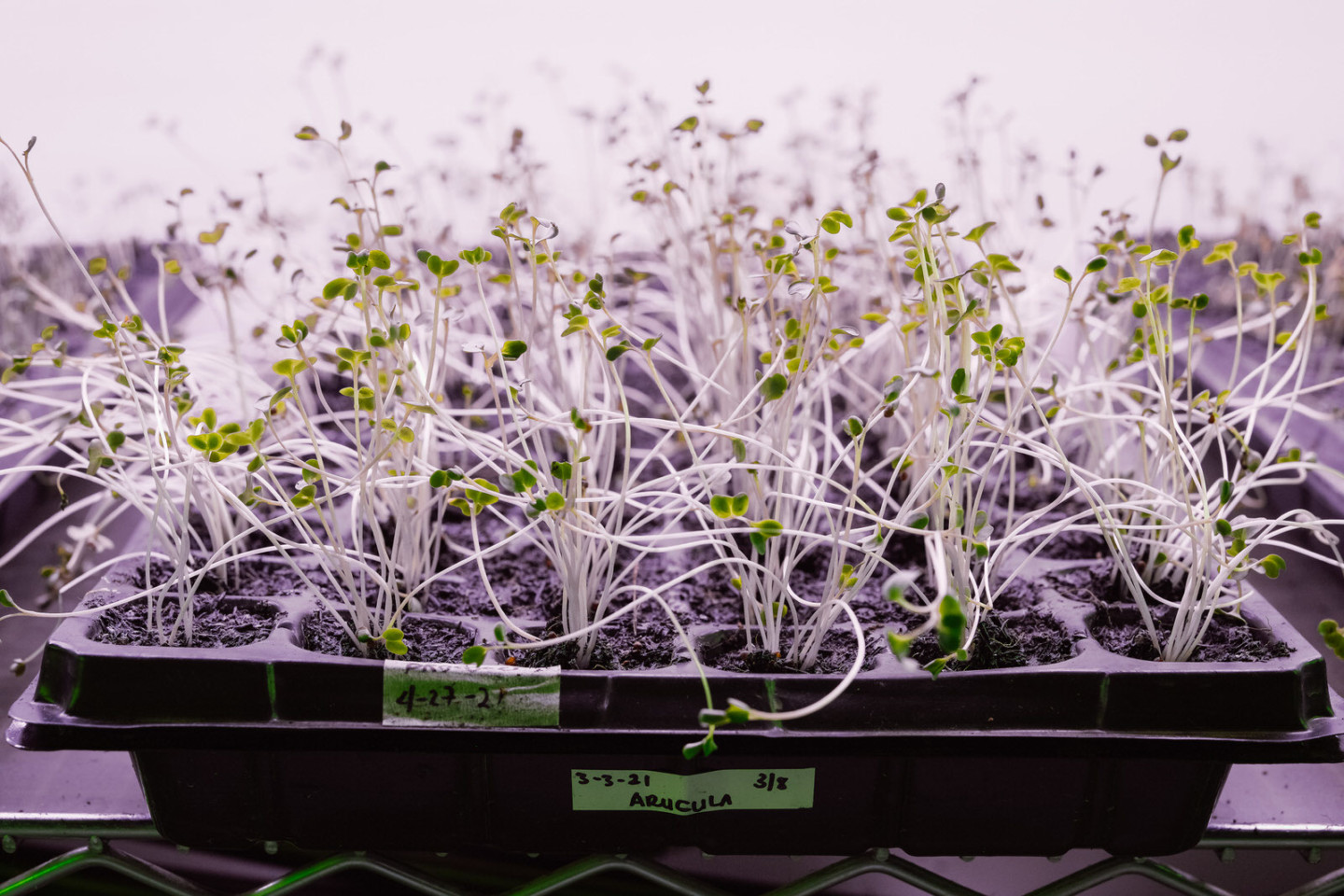

Derya shares that Rocket Arugula was their first produce of choice. “We also asked around, interviewed friends and restaurant owners, and then moving on from there, our product selection grew from conversations with customers. We love speaking with our customers. ‘What else are they interested in?’, ‘What would they buy?'”

At present, Future Fresh has a farm in Quezon City but is also developing another one in Taguig, which will be operating in May. It will be bigger at 800 square meters and can produce up to 5 tonnes of produce a month with 16 of their containerized systems, tripling their current capacity and yield.

“In terms of next-generation farming, customer excellence and sustainability matter above all else. Another thing we’re doing is that we have created a research and development lab, which is very exciting to improve our technology and expand into new crops and produce. This is where we can innovate and build new efficiencies without disrupting our production at the farms.

Both Ralph and Derya have shared plans of expanding throughout the Philippines and the region, pushing for better agriculture everywhere through their homegrown indoor farm systems. Our growing cities need to be more conscious about what it means to sustain life because if not given proper attention and action, the urban food system will continue to be vulnerable, especially in times of health, economic, and climate crises. In a future that keeps developing, our need for more farmers is made even more clear.