From being a fresh advertising graduate exploring teaching at the University of Santo Tomas many years ago, Mark Salvatus has grown as a prolific artist engaging in various creative and artistic pursuits across local and international contexts such as at Load Na Dito Projects, an initiative he co-founded with independent curator Mayumi Hirano, and Boy Agimat, a self-conceived merchandise project with products ranging from collaged shirts from second hand clothes, tote bags, purses, masks, to patches and stickers.

We’ve had the opportune moment to visit Mark in his studio in Quezon City and had an insightful conversation on his artistic process and practice, his key to sustaining it through these years, and his belief in blurring the lines in art and everyday life.

Your body of work consists of many process-oriented creations or a presence of iterations or a continuance such as in Scratching Paintings (2017-ongoing) and Salvage Projects (since 2006), can you walk us through your process?

My father collected many random items which formed the environment where I grew up. Our house kept transforming as he constantly added objects and souvenirs from thrift shops like vinyl records, books, magazines, local comics, photo prints from the 70’s and 80’s, old watches, radios, santos (saints), and other knickknacks. It had accumulated throughout the years and became part of our everyday life.

My grandfather, a poet, local historian, and public school teacher, also left a lot of clippings of his writings, songs, photographs, magazines, and notes. These gestures of digging, writing, and collecting triggered my mind to imagine objects or ideas as an extension of our body and life. These objects and ideas produced in different times also formed a constellation, which I became part of. They became the material for my inquiry of life and art practice.

This opened the possibility to reconstruct or deconstruct complex meanings of life. I also learned to embody the spirit of ‘picking/picking-up–in pieces, in series, in rhythm.’ The annual tradition of Pahiyas festival in my hometown has largely influenced how I produce works. There were no museums or galleries in Lucban, Quezon when I was growing up, but this communal celebration of hanging vegetable and fruits and any readily available materials in the immediate environment taught me creativity, continuity, ingenuity, and transformation as the keys to survival.

Would you have any specific strategies in terms of sustaining your practice?

I moved to Manila to study Advertising, a course of visual and communication application. This opened new knowledge about “how we look” at things, how it [advertising] creates energy and meanings, and eventually changes our behaviors. Meanings are produced through communication and miscommunication. Advertising, though, intends one-way communication. It tells us, the viewers, to consume.

But what we shouldn’t forget is that we have the right to choose. I am interested in the circulation and movement of ideas that is organic and bottom-up that can transform spaces and our perception about different things. Movement is also about people and the aspiration to connect to a new place.

Through my work on graphic design and illustration, I explored street art. The public space became my site of exploration and play and production and presentation at the same time. As I started approaching the street as my studio and getting involved with street art community like Pilipinas Street Plan (PSP), it gave me the opportunity to learn and unlearn the different ways to co-exist and survive together.

Sustaining one’s own art practice is a matter of life and a critical decision. It’s a process of asking oneself what really matters and what is important in one’s life. I came up with “Salvage Projects.” I envisioned it as a patchwork made of my small gestures and interactions with different materials. It retains the state of unfixed and fragmented, which I guess are the opposite of what art is supposed to be – stable, long-life, secured, and complete. Salvage means to save, but in vernacular Filipino context, it refers to extra-judicial killings. I am interested on how this word has innate conflicts, and my projects try to examine this tension that is always open to different possibilities.

And just to add, salvage/salvation is also the meaning of my surname.

Your fascination and engagement with familiar objects and contact with mundane is predominantly present in your work and your academic background is advertising. Would you say these relate to or have influenced the idea behind Boy Agimat?

Since I started as a street artist, I see the urban landscape especially Metro Manila as a site to examine my unstable position in the city and how I’m constantly influenced by the social forces. When I was still new to Manila, as what you call, bagong salta, I had to adapt and familiarize myself to be able to navigate the city. It was my father who told me that if I ever lost my way, just ride a jeepney with a Quiapo sign on it and you will be at the center of Manila. Because of being lost, I became more aware of the things around me—objects, signs, sounds, and visuals that are used in everyday communication as signals to create relations. Trying to remember the contours of the city, it led me to form Boy Agimat.

My idea was formed based on the agimat sold beside the Quiapo church—a small amulet based on one’s faith or pananampalataya. I also connect my fascination with agimat through the Filipino hero Apolinario Dela Cruz also known as Hermano Pule, a native of my hometown who led a small but significant uprising against the Spanish colonizers. He and his followers incorporated elements of pre-colonial pagan beliefs such as the use of anting-anting or agimat. I started to post Boy Agimat stickers as a sign of being lost instead of being seen.

As Boy Agimat, how do you usually come up with designs and eventually translate these into actual objects?

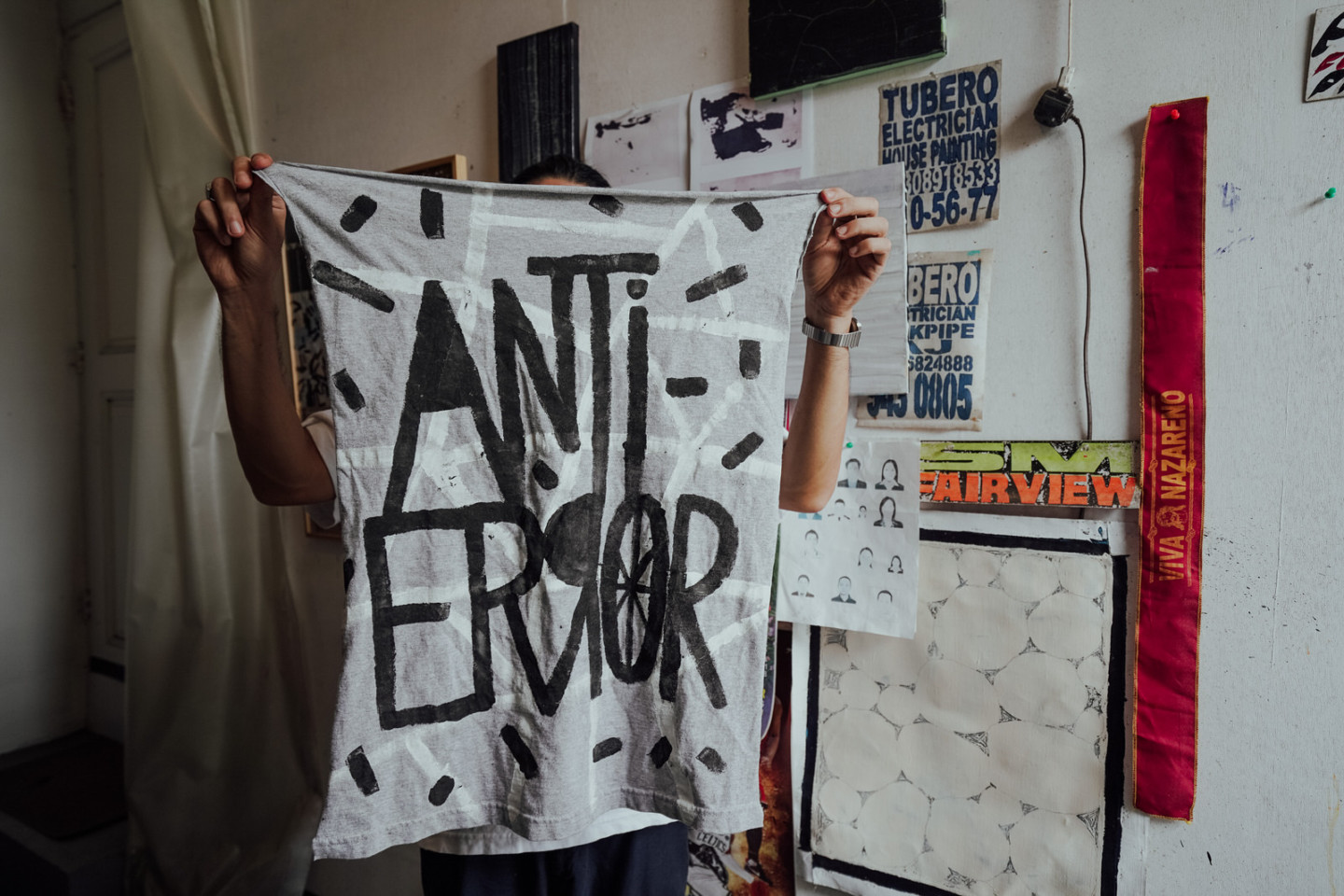

Aside from the stickers, posters, and artworks of Boy Agimat, I make products that can be sold. As much as possible I make the products small, wearable or something that can be kept close to the body—like a coin purse, bag, pins, t-shirt, patches, and pillows. It is something that you can carry, like agimat, as a charm and protection. I work with local seamstresses in Lucban, and it is coordinated by my mother. My brother takes care of printing, so everything is made in Lucban. I have this dream of having a shop of Boy Agimat merchandise with second-hand items.

Do you have specific references you consider most influential in your practice?

When I was still in college, I met artist Alfredo Aquilizan in an exhibition opening in Manila. I didn’t know him that time and maybe he doesn’t remember this happened. He asked me what I do, and I told him I was studying advertising—doing graphic design, illustrations, graffiti and some paintings too. And he told me, “You should do installations.” From that encounter, while standing and holding my plate of pika-pika, I got interested and researched what “installation” is. I got to know more about Alfredo and Isabel Aquilizan and really saw an instant connection to their practice of collecting—participatory and site-specific. I consider them as an indirect mentor. Eventually we became friends and were part of several shows together. That small talk really influenced how I am now as an artist.

I also became part of an artist collective called TUTOK, and it was through this initiative that I learned to organize and to come up with exhibition in different formats. There I met and worked with Karen Flores, Noel Cuizon, Manny Garibay, Jose Tence-Ruiz, and Mideo Cruz, along with other artists of my generation. Through this collective and DIY spirit, TUTOK introduced me to the potential of art and artists in creating conversations about important social issues in the Philippines. Through meetings and dinners, I met a lot of artists, activists, and other cultural workers not only from Manila but from different parts of the country. My involvement in TUTOK helped me in coming up with other initiatives like 98B COLLABoratory and now Load na Dito that impart sharing, exchanges, and participation.

Your artistic articulations are prolific and continually explorative, is there a specific mindset that you follow? Has this been your ‘plan’ or trajectory in mind when you are in your early years as an artist?

I took many jobs, tasks, and roles when I was starting to be an artist—from graffiti to teaching. There’s even a point in my practice that I contemplated if I should separate Boy Agimat from my own “art-making” and it’s a constant dilemma I used to face. I told to myself that I should not categorize or shape my practice in a single linear direction.

It’s interesting not to plan, not to be strict, not to be stiff. I am interested in blurring the lines between the high and low, public and private, intimate and the vulgar, and I want to experience these nuances and ambiguity that are sometimes ignored. As I lived and worked in the city half of my life, I am longing for the countryside, the mountain, and its significant subtleness, but I have only one body. I cannot be in two places at the same time, but my spirit can be in many conditions and place—imagining, thinking, aspiring and I think that’s working for me now.

As an artist, what’s the most important piece of advice that you could give to emerging creatives?

Be persistent rather than consistent. Being an artist is not only about how you work as an artist, but it relates to almost everything that you do. I always see that there is no right or straight direction. It’s not a paved way. It’s like an immense open sea or a huge mountain; we have to sail or trek the contours and the waves, through which meanings and energy are produced.

It’s the same with art making; we get lost, frustrated, happy, and we accidentally find things, meet strangers—use all of these as your own unique material to create your visual language. It’s about developing a language that is open to anyone who wants to be part of your journey. Another thing that guided me in my art making and practice is, to have the element of humor and play—be serious to play and be playful to be serious.

Photographer — Zaldine Alvaro

SUPPORT PURVEYR

If you like this story and would love to read more like it, we hope you can support us for as low as ₱50. This will help us continue what we do and feature more Filipinos who create. You can subscribe to the fund or send us a tip.

1 Comment

Add comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] later, he became part of Pilipinas Street Plan (PSP) (where Mark Salvatus and Auggie Fontanilla were a part of as well) as one of the first contemporary artists in the […]