More than 2600 businesses on Instagram alone describe themselves as LGBTQIA+-owned or LGBTQIA+-friendly in the Philippines, but what does it really mean to advocate for the LGBTQIA+ community?

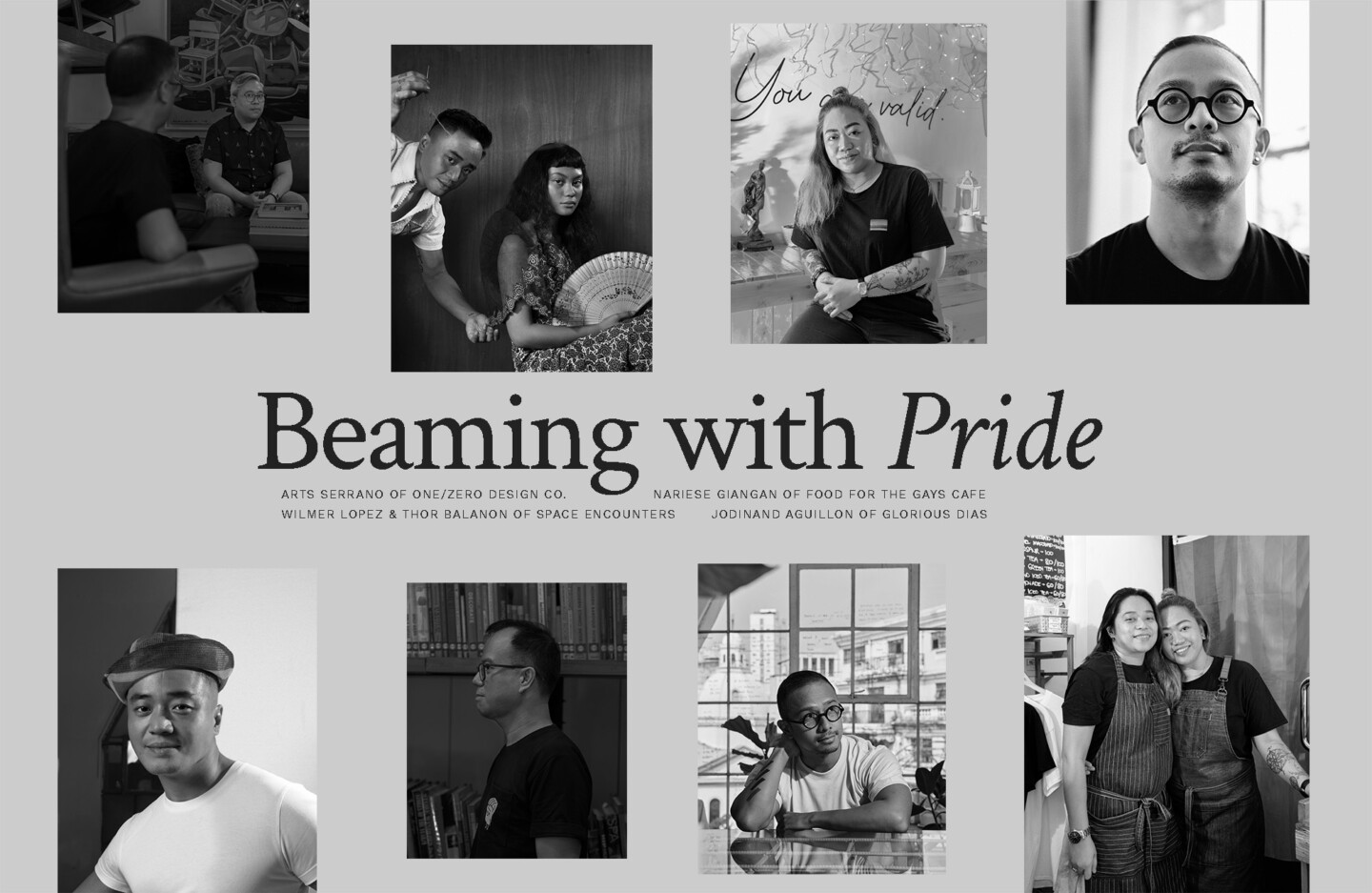

In partnership with Meta, this Pride Month, we feature dynamic individuals from the LGBTQIA+ community who are making great strides within their respective industries, thanks to the way they do business: Arts Serrano of one/zero design co., an architecture and design studio; Nariese Giangan, co-owner of Food for the Gays Café (FFTG); Jodee Aguillon, the man behind Filipino vintage shop Glorious Dias; and Wilmer Lopez and Thor Balanon of Space Encounters, an interior design firm, mid-century modern furniture store, and art gallery.

“Our platforms are a place where everyone can find their power and their voice to truly express their authentic selves and push for causes that matter. This Pride Month, we are championing members of the LGBTQIA+ community who are shaping the future of business, tech, culture, community, and gender expression across Meta technologies,” says John Rubio, Facebook Philippines Country Director at Meta. “We are committed to creating opportunities for the LGBTQIA+ community across the Philippines to build connections and tools to achieve progress while ensuring easy access to resources.”

It’s never business as usual for these inspiring individuals—from creating safe spaces, breaking stereotypes, increasing LGBTQIA+ visibility, to empowering kindred souls, one/zero, FFTG, Glorious Dias, and Space Encounters have evolved to serve greater purposes.

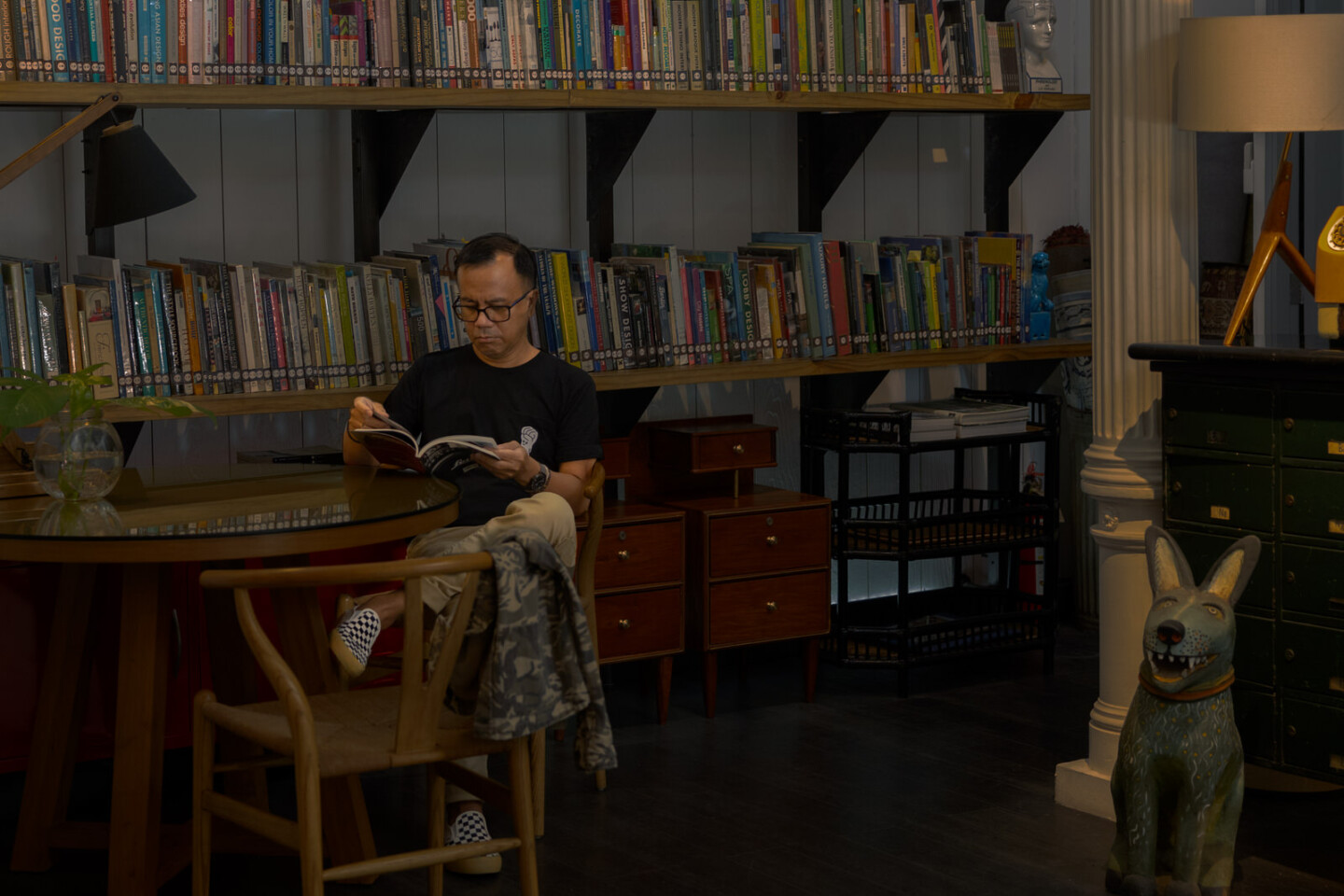

Arts Serrano photographed by Renzo Navarro

You’ll be Safe Here

At one/zero, Arts nurtures an office environment where all kinds of identities and creative expressions are welcome. The architect notes that not only does this broaden their perspectives on their design practice, but it also encourages authenticity and ingenuity among team members.

“I always encourage the team to explore creative endeavors outside the studio,” Arts shares. “I believe that when we allow different parts of our personalities to thrive, we get to be more creative and authentic about ourselves, [which then reflects in our design practice.]”

Such opportunities abound in Escolta, the home base of one/zero. With establishments such as the HUB: Make Lab and events like the Escolta Block Party, the street becomes an empowering safe space for a spectrum of expressions and identities. Even Arts himself experienced how this creative space motivates an individual to be their authentic self.

“I only became transparent about my sexuality in my second year here in Escolta—around 2017,” he recounts, also noting how he comes from a generation that isn’t as open about their sexuality. “Architecture and construction is generally a male-dominated industry. There is discrimination [toward] people expressing queerness—normally, [it is] seen as a sign of weakness.”

But by being immersed in a space like Escolta, Arts saw a diverse cast of creatives who embraced and expressed themselves unapologetically. “I felt bad [at the time] na andito ako, pero tinatago ko yung sarili ko (I was here, but I was hiding my identity). So since 2017, I made it a point to lead a studio that would be open to who we are as individuals.”

Similarly, Thor and Wilmer consider it instinctive to create a creative work environment at Space Encounters where their employees feel safe and protected. “Space Encounters has always been a safe space for the LGBTQIA+ community. They can come as they are. No dress codes. We just want everyone to be [at home] in their own skin, because when the designers are comfortable, they can truly make magic,” they say.

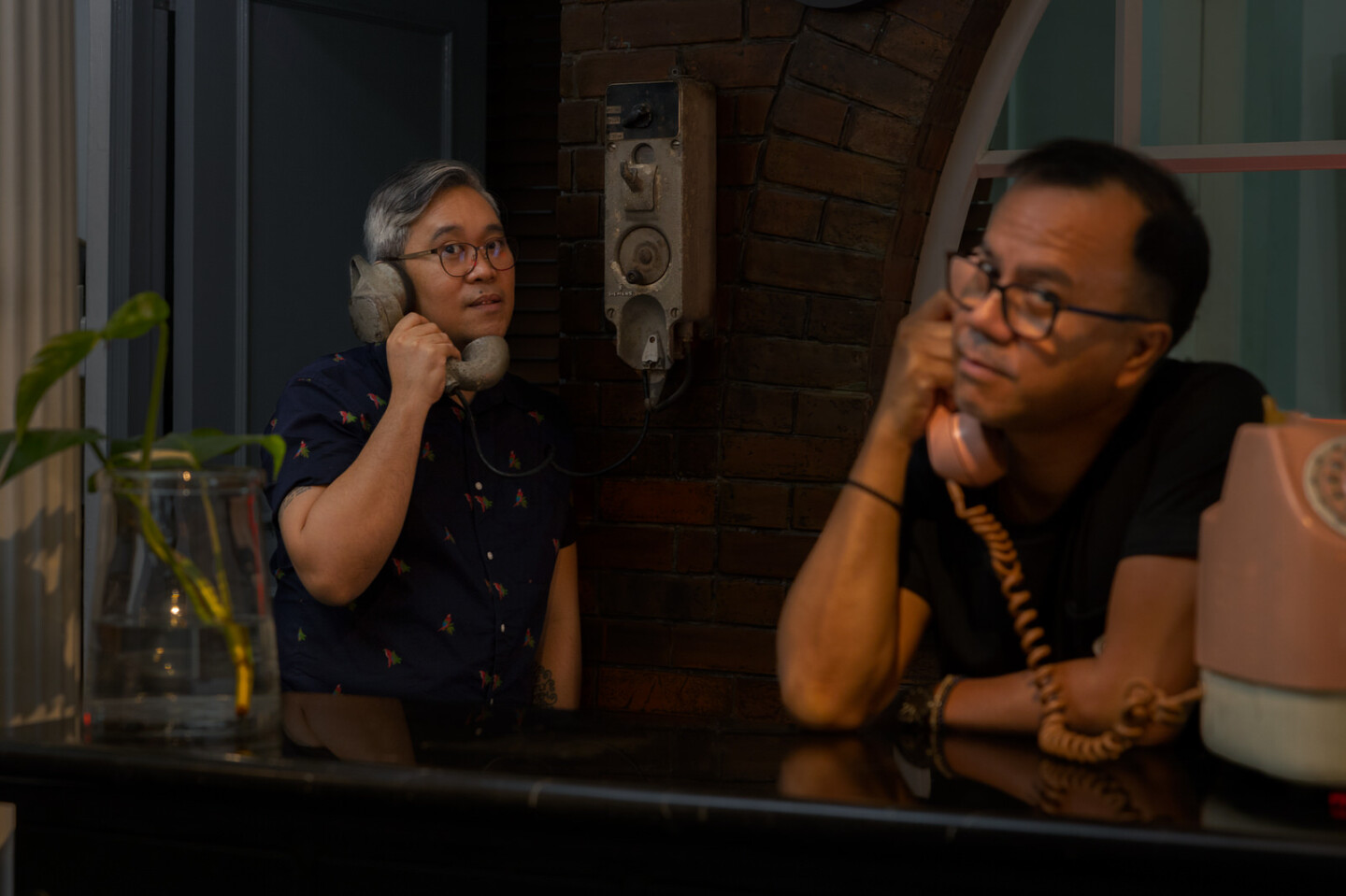

Thor Balanon and Wilmer Lopez of Space Encounters photographed by Koji Arboleda

To maintain this working environment, Thor notes that they have systems in place to deal with discrimination and ignorance. “If we have members who make [offensive] or homophobic remarks, they are immediately corrected on the spot and are later set aside to discuss what they had done wrong. If this becomes persistent, then that employee does not belong to Space Encounters,” they add.

Understanding that discrimination is an unfortunate reality for members of the LGBTQIA+ community at large, the owners of Space Encounters go the extra mile to foster a creative safe space that also safeguards their team’s emotional well-being.

“You cannot choose what you encounter outside. Kasi pag nasa labas ka na, you’ll be on your own” says Wilmer. (When you’re already outside, you’ll be on your own.) “As the president of Space Encounters, I’m very protective [of my employees—not just with their] sexual orientation, gender identity and expression (SOGIE), but [I protect them from clients, if needed,]” he further adds, sharing how he goes as far as personally speaking with people who may be giving his employees a hard time.

“Every day, [our team faces] challenges. But if we are in Space Encounters, we are in our shelter—here, there will be someone who will listen to [you]. That’s how I want to make them feel like—that I’m really taking care of them,” he adds.

Nariese Giangan photographed by Cru Camara at Food For The Gays Café

Meanwhile, when Nariese opened FFTG in 2021 with her partner Chippy Abando, they already knew that they wanted to become a safe space for LGBTQIA+ folk. As such, they designed the café to be as cozy, welcoming, and open as possible. But it wasn’t until they had meaningful interactions with their customers—some of which have become regulars—that they realized how important it is to continue nurturing and deepening their understanding of safe spaces.

“Para maging safe space ang isang business, dapat magsimula ito sa owners hanggang sa staff. Hindi lang siya dapat tungkol sa espasyo—ang safe space kasi ay maaaring tao o isang samahan,” Nariese explains. (In order for a business to become a safe space, the efforts should begin from the owners to the staff. It’s not just about literal space—safe spaces can also be a person or a fellowship).

Understanding that many LGBTQIA+ folk do not feel welcome in their own homes, FFTG strives to extend that feeling of warmth and ease. “We [do] our best to make our customers and friends feel that we accept them and that we will never judge them. That’s what we are trying to do here at FFTG. We are slowly trying to build a community, a collective, a family.”

And most recently, Nariese has reflected on the role of their personal values—political, social, among others—in strengthening or defining a safe space further. “[Importante rin na makasama yung] values, mga paniniwala, at mga paninindigan namin. Yung kapag nalaman ng customers namin na ‘ah, [pareho rin kami ng paniniwala,] kakampi nila kami, ipaglalaban nila kami,’ [mas nagiging] kumportable sila, [mas ramdam nilang] safe sila dito,]” she says. (It’s also important to incorporate your values, beliefs, and convictions. When our customers learn that they share the same ones as ours, they’d feel more at ease. They’d think, “all right, they’re our allies. They’ll also fight for us, with us.)

Cru Camara captures Food For The Gays Café, Nariese Giangan with partner Chippy Abando, and the duo with their friends

“Malaking bagay na safe space nila kami, at safe space namin sila,” Nariese adds. “Kapag alam namin na andito sila, napapalagay din kami kapag pumupunta sila dito.” (We think of our customers as our safe space too, as much as they treat us as such. We feel at ease as well whenever we see our regulars.)

For Jodinand, more known as Jodee, safe spaces are the perfect avenues to channel the voices of the marginalized.

“There always needs to be a greater effort to shine the spotlight on the fringes of what the mainstream is focusing on. It is important that safe spaces—brave spaces—become a beacon for people to go to, [a space] to meet like and “un-like” minded people within their sphere,” he says.

For instance, more than providing access to vintage Filipiniana and goods, Glorious Dias supports fellow LGBTQIA+ creatives by using its physical and digital spaces—from featuring local brands in the store to highlighting fellow queer creative work on its socials.

As a queer Filipino-Canadian, Jodee has access to distinct and different experiences of Pride and queerness. Drawing from this intersectionality, the artist stresses that safe spaces for LGBTQIA+ folk must seek to address and challenge the margins even within the community.

Jodee Aguillon of Glorious Dias photographed by Cenon at Mav

“[More than focusing] externally, if we look internally and strengthen those connections, learn the stories and backgrounds of the spectrum of identities, then naturally, people who don’t understand [the spectrum] would want to be part of something special and organic—a genuine community that supports one another,” he says.

The interdisciplinary artist further explains that the work that he does has always been tied to that sense of community. In particular, Glorious Dias, which was born in the creative hub Pineapple Lab, finds homes now in HUB: Make Lab and Common Room PH—both of which house and nurture a variety of identities and creative talent.

“Glorious Dias is not a standalone retail experience—it has always been part of a bigger community, a bigger idea. The retail is there—there’s no denying that it’s a business—but I don’t think that I can wake up and find meaning in my work—if it wasn’t tied to the community,” he notes.

Arts Serrano at the one/zero design co. studio photographed by Renzo Navarro

Let’s Get to Work (and Werque!)

More than instinctively creating safe spaces that allow a spectrum of identities and creativity to thrive, Arts notes that queerness (and unapologetically showing it) adds an extra spark in how they do their work.

“We think our queerness adds more fire for our studio to attempt to do things differently. Our very existence is oftentimes othered, and for us this manifests in design solutions that challenge the status quo. Our existence and how we express ourselves is naturally intertwined with how we work,” he says.

But while one/zero encourages out-of-the-box ideas and forms of expression to thrive, Arts acknowledges that certain forms of resistance (mostly unintentional microaggressions, and not so much deliberate expressions still take place in their practice.

For instance, Arts has observed that in construction sites, the contractors or workers would approach him for questions instead of the actual project lead or manager who happens to be a woman or a queer individual.

“Whenever I feel that [our colleagues] would set aside the person assigned for the [project,] I try to navigate it in a way that I would answer their questions, but also include my project lead back to the conversation,” Arts says. “Kapag nangyari yung [hindi ka kausapin,] you’d clam up. So I try to bring back that team member and involve them more. It helps build that confidence and trust in them.”

Cenon at Mav captures Jodee Aguillon with model Clarisse Furio

Jodee echoes this idea of being unapologetically queer in the way one does their work.

“It’s important to understand that queer is who I am, while work is what I do. [The business] is how I make money. So, can I separate the two? Sure. Do I want to? No. If I’m going to express my POV, it must be genuine. To not include [my being queer] wouldn’t make sense because I wouldn’t enjoy it,” he says.

He adds: “There’s a reason why I don’t sell streetwear T-shirts. There’s a reason why I don’t sell sneakers—it wouldn’t be me. There is a reason why [Glorious Dias] looks like Lola’s or Mama’s closet and not necessarily Lolo’s or Dad’s closet.”

Moreover, Jodee looks at the constant othering that queer folk experience as a driving force toward two things: being excellent and choosing to go freelance. In Jodee’s case—growing up as an immigrant queer kid in Canada—this drive to be great to compensate for otherness was a strong driving force in his life.

“When we talk about the fabulous and the magical and everything else associated with being queer, I think there’s always this expectation: if you’re queer, then you must be excellent,” he surmises.

“How does this translate into business? When you’re within a unique point of view, it lends itself well to becoming self-employed, because there isn’t a path that you want to take. The ones that are laid out for you don’t speak to you. So naturally, you would want to create your own lane. That translates perfectly to someone who wants to freelance or open their own business—they want to create something that isn’t there yet.”

Thor Balanon and Wilmer Lopez shot around Space Encounters by Koji Arboleda

Interestingly, Thor and Wilmer look at queerness as an advantage in interior design—a profession that they say is perceived as “feminine.” “If you are a male interior designer, people will immediately assume that you were gay. [But] being queer is an advantage in this profession because one can create both masculine and feminine spaces,” they say.

“Salon clients seem to be more comfortable working with queer designers—this is when stereotypes play to our favor for once. But Space Encounters is also known for its masculine, industrial spaces. It’s the best of both worlds, so to speak.”

Queerness also makes itself present in the exhibits that the pair present at the Space Encounters Gallery. Four years ago, they mounted an exhibition that celebrated the 16th year of queer superhero ZsaZsa Zaturnnah. Commissioning several artists to make their own interpretations of Zaturnnah while inviting designers to craft furniture pieces, they were able to create what was hailed by the media as a “significant cultural moment.” An all-queer exhibition is in the works, and they plan to hold it in next year’s Pride Month.

“Representation has had a strong impact on young queer designers. If they see that queer-owned businesses [and individuals] are flourishing, then they feel more confident to join in and let their voices be heard. Our queer staff feel more comfortable sharing their ideas with us, including personal difficulties that they are going through, because we, they say, simply get it,” they note.

Drawing from her experiences in FFTG, Nariese thinks that queerness—more so, the shared experiences that LGBTQIA+ folk know all too well—translates into more genuine care and concern toward their own businesses, staff, and customers.

“Almost all of us have experienced discrimination or harassment. We know how to take care of our own people. We understand each other’s struggles,” she says. “I guess aside from the business side, andun ‘yung genuine na care at pagmamahal sa mga tao [na] mararamdaman mo kaagad. [Nadadala namin] ito sa pag-serve sa mga [customer].” (I guess aside from the business side, you’ll find and feel that genuine care and love for people. We get to translate this in how we serve our customers.)

Nariese also admits that this stems from her own childhood experiences. “It wasn’t easy for me to find true friends because I was different. So, I made it my personal mission to guide and be a role model to younger LGBTQIA+ folk. Ayokong may naiiwang mag-isa. (I don’t want anyone to get left behind). I wanted to be the person that I wish I had growing up.”

Being hands-on with the business allows Nariese to do just that and more. “When you genuinely care for your customers, they will immediately recognize that. It’s nice when you try your best to memorize their names and talk to them—it goes a long way. And we always see to it that we celebrate each other’s achievements, kahit customers pa ‘yan or other queer business owners.”

The Future is Queer

What is the future of a queer-owned business? It’s an exciting future that should still be approached with cautious optimism and patience.

While not a personal account, Nariese shares a sobering reality: “May ibang sobrang wild ng ginagawa sa kanila ng mga tao kapag nalamang queer-owned ang business, umaatras [yung] orders or reservations. Kaya minsan kailangan talaga doble o triple kayod sa pagprove ng mga sarili sa mga tao bago tangkilikin. Kasi nandun pa rin yung prejudice ng mga ibang tao.” (There are some crazy cases I know wherein customers cancel their orders or reservations when they learn that the business is queer-owned. That’s why sometimes, queer folk have to work doubly or triply hard to prove that they’re a business worth patronizing, because people’s prejudices are still there.)

But at FFTG, they seemed to have found one viable solution. “Sabi ko nga noon, minsan baka way ang good food and coffee para maging mas accepting ang mga tao. Straight people also come to our cafe. Sometimes they don’t just order food. They also ask questions kasi very curious sila. I think it’s a good way to open the conversation,” Nariese shares. (I used to say that perhaps good food and coffee are ways to make people more accepting. Straight people also come to our cafe. Sometimes they don’t just order food. They also ask questions because they’re genuinely curious. I think it’s a good way to open the conversation.)

Portraits by LGBTQIA+ photographers Renzo Navarro, Koji Arboleda, Mav at Cenon, and Cru Camara

And if we need any proof that sticking to one’s principles and being unapologetically queer works, we can turn to Thor and Wilmer. “Our HR mentioned that she is proud to belong to a queer-owned business that has succeeded without compromising its morals [adjusting] to a heteronormative society,” they proudly share. “Just the fact that we’ve been here for more than ten years making design and art accessible while creating good, intelligently-planned spaces and healthy and nurturing work environments means that queer businesses are here to stay.”

For Arts, he hopes that by openly discussing queer issues through the lens of an architectural studio, people from the design and construction industry may begin to acknowledge that one’s SOGIE does not limit a person’s ability to function as a professional. “Once we remove ourselves from the binary, we can be more receptive to a wider range of design expression,” he says.

And LGBTQIA+ individuals who wish to make it in business—or whatever industry they want to thrive in—Jodee doesn’t mince any words:

“Be excellent. Do the work and understand that it’s the people who didn’t follow the book who created paths for us and others to follow. As the generations before us were creating safe spaces for themselves, they were [unwittingly] creating even safer spaces for the next generation. So, you have to look forward and back and understand what role you must play in the whole timeline.”

SUPPORT PURVEYR

If you like this story and would love to read more like it, we hope you can support us for as low as ₱100. This will help us continue what we do and feature more Filipinos who create. You can subscribe to the fund or send us a tip.