Art is a tool for social change. One can typically relate this statement with a certain artist or a specific art movement in explaining this testimony. But perhaps this is a good way to think about it first: What do we mean by social change in our very own personal life? In celebrating the 37th anniversary of the EDSA revolution, it is not only important to revisit and to never forget our history, but also to understand how creativity and social awareness are crucial in recognizing our own self as part of societal change.

The life of artist Federico Dominguez encapsulates the exact relationship between art, life, and society.

Federico Sulapas Dominguez, also known as “BoyD” among his friends and colleagues, does not only make art that reflects social injustice but also lives by the principle he believes is essential to countering such unjustness. Having been born in Bukidnon Province and raised in Davao City, Dominguez unconsciously found himself surrounded by the realities of a societal tension that will eventually shape his impression towards authority and his privilege as student and artist. He studied Practical Electricity in a vocational high school, eventually enrolling in an Architecture course at the University of Mindanao, where he was able to hone his skill in drafting which later on gave him an opportunity to work under a non-profit organization during the 70s governed by a certain crony of then President Ferdinand Marcos, Sr.

He was naive of the ulterior agendas of the administration he was working under. Soon after, BoyD would also see himself joining and listening to educational discussions in his community in the district of Agdao led by members of a political group that came from Manila. Such discourse would initially make him realize the atrocities and interconnected events that are happening in his immediate surroundings—where he was working and what conditions he has been living with in their urban poor community.

He then had the opportunity to travel to Manila to work for an assignment as part of the construction for the Manila Film Center—national building and main theater project by then First Lady Imelda Marcos. The Film Center with an allotted budget worth millions and built to host the 1982 Manila International Film Festival eventually made local and international headlines with the November 1981 tragedy when its scaffolding collapsed costing the lives of around 169 workers. This underpinned his realization about social inequality brought by the ongoing dictatorship of the Marcoses.

Taking the first step

This realization extended to his curiosity towards art and its relation to society. This was later on cemented by his exposure to artistic growth as he enrolled at the College of Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines (UP) to study Visual Communication in 1986. Although not yet a member of any art or socio-political organizations, BoyD remained aware and well-acquainted with various groups such as GAT (Galian sa Arte at Tula) which is considered as one of the most active organizations of young writers back then and whose founders are well-known writers in Philippine literature: National Artist Virgilio Almario, and Palanca awardees Teo Antonio and Mike Bigornia. Dominguez also met a group of visual artists called ABAY (Artista ng Bayan) whose members include Egai Fernandez , Neil Doloricon and others.

He was an active observant with a consistent attentiveness on the real conditions of his environment. This is evident with his participation in the series of protests in February 1986, known as the EDSA Revolution or People Power Revolution. The revolution was provoked mainly by the 1983 assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr., the 1986 snap presidential election fraud, and decades of oppressive ruling of Marcos, Sr. Dominguez was one of the estimated two million people who gathered, walked, and marched along the Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) for the peaceful revolution that ultimately ended the Marcos dictatorship. Albeit going with no group, BoyD went to protest to join his fellow art scholars and professors—perhaps as a culmination of his personal reflection towards his understanding and analysis of what really was happening around him.

Dominguez witnessed first-hand the turn of events in Philippine history brought by EDSA I. While at that time he was a more of a participant, the event shaped him to become the artist-activist that he is now. Around the late 80s, he became a member of progressive organizations such as the Concerned Artists of the Philippines (CAP)—an organization of artists, musicians, writers, and cultural workers committed to advancing freedom of expression and the people’s movement for justice, nationalism, and democracy.

Organizing oneself as part of a group

For BoyD, joining progressive groups was an important aspect in organizing oneself within the concept of collective action—any occurrence involving a group of people that work together to achieve a common social or political objective. Dominguez also strengthened his artistic self and experience within a community that are united by a particular political belief—of the Marxist perspective. This is greatly evident in his narrative works that portray the peasant life signified by the indigenous peoples and agricultural workers juxtaposed with the capitalist and imperialist entities that disrupt the development or capacity to progress of the rural landscapes of the Philippines, especially around agrarian struggles.

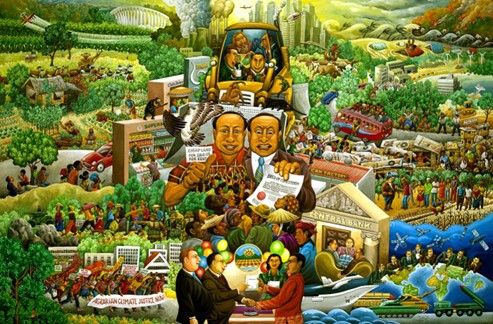

One example would be his untitled 2020 tempera on watercolor paperwork which reveals the complicated layers of agrarian development that include conflict and tension brought by the contemporary feudal system.

Dominguez’s 2020 untitled tempera on watercolor paper work. Image from Federico Dominguez.

Study of Tumbang Preso’s float for a 1998 demonstration. Image from Federico Dominguez.

His other creative projects would also come in the form of propaganda which varies from creating posters which serve as medium for call-to-action and making effigies through collective efforts of fellow artist-activists. A design study for the Centennial commemoration of the 1898 Philippine Revolution rally in 1988 illustrates the continuous fight for genuine national freedom of artist-activist group called Tumbang Preso—a formation of artists where BoyD was a member of.

Continuing the responsibility for social awareness

Today, BoyD still pursues his passion in the arts while also keeping his networks close to his fellow artist-activists then and the new generation of artist-activists today. He is frequently seen visiting and mingling with other customers, staff, and friends who visit and eat at Terra Bomba, a bistro in Matimtiman Street in Quezon City. At the age of 69, he still involves himself and contribute to artistic projects, gatherings, and assemblies. He warmly welcomes conversations and gladly share his experiences and learnings specifically his encounters about shared cultures with his travels and research in Southeast Asia.

Federico Dominguez’s beginnings as an artist-activist, among other artists’ stories, is a relevant insight for today’s generation of artists. As he always believes, “Mayroong pag-asa para sa pagbabago.” Witnessing the first EDSA Revolution unfold during his formative years as an artist and scholar, BoyD realizes his role in contributing towards achieving social change. The 1986 social unrest is perhaps one of the pivotal events for Dominguez to re-examine himself as an artist and as a member of civil society—something valuable for today’s generation of artists whose sense of social and artistic self must remain proactively aware of what is within one’s surroundings.

BoyD’s ongoing practice is a reminder of the role of the artist-activist which continues to persist as part of the struggle of the whole community. In this sense, there is also a reminder that the annual commemoration of the People Power Revolution is not a holiday for rest, but to reflect as well on the self in one’s role within social unrest.

CREDITS

WRITER Gian Carlo Delgado

EDITOR Tricia Quintero

PHOTOGRAPHER Zaldine Alvaro

SUPPORT PURVEYR

If you like this story and would love to read more like it, we hope you can support us for as low as ₱100. This will help us continue what we do and feature more stories of creative Filipinos. You can subscribe to the fund or send us a tip.