There are reams of data available creating a canvas of The Philippines as a difficult place to do business. Start with points on the grossly inequitable distribution of income, and you wind up wondering where the market for your product could be. Embark on fulfilling the mandated government and tax requirements for registering a business, and you quickly begin fielding questions around why you wanted to try business in the first place. Get your product up, running, peddled off on the internet or in a store, and so run into the mad task of spinning hundreds of plates in the air all at once.

Business is a tough game to play.

But, spitting in the face of adversity and smirking at the task of creating something of value, the entrepreneur remains undaunted–battle-hardened–but optimistic that the fruit of their creative labours finds the sun of a robust and sustainable consumer base.

Bridging artists on the fringe and deep in underground subcultures–from the graffiti to skateboard scenes–with markets that can appreciate their work has been the goal of artist-run space and initiative Kalawakan Spacetime since its founding in 2017. But that task, the devotion that comes with navigating “the mundane”, i.e. the admin and bills, to launch the careers of artists takes hope.

Jan Sunday Paloma of Kalawakan Spacetime

“[There’s] so much sacrifice for something creative or something passion based,” says artist and Kalawakan Spacetime partner Jan Sunday Paloma. “If it’s driven by passion, you really [need] to have faith that it’s ‘gonna work out.”

And with that faith in the business comes a series of decisions that business owners need to make on a daily basis and at cardinal moments of their business’ lives. This is the task of tending to—of minding–their businesses. This has the entrepreneur suspended with a gentle balance of available resources, business insight, and an inevitable smear of difficulties standing between their customers and their products.

It’s worth noting that we are participants in this ecosystem. The entrepreneur can’t exist in a vacuum. We play the role of consumer; better yet, of promoter–of champion even–or as collaborator. And so beckons our task of paying attention to—of minding—their businesses.

Attention to the Product and the People Buying it

With a country crippled by stark inequality, understanding where the market for a product is is difficult. While there is an argument over whether our country has a real unicorn in it or not, it’s an interesting point to ponder: the largest “startups” in the country are payment processing giants. The companies worth a billion bucks are those that transfer money from person to person, the building block of commerce.

For the rest of the small business community, entrepreneurs can’t but focus on huddling their brands closely around where they can actually flourish. Even if that means moderating the pace at which their operations scale. Abraham “Finn” Finney Santos of Freedom Print Lab and cult-followed Nobody shares, “I think that’s an aspect that sometimes gets missed, your scale versus the work you accept.” After all, the success of his brands has come through striking a strongly resonant chord with the market. “We do good work,” he shares. “We do work that I think is smart, something with layers of meaning, and mostly things that [are] referential to our local environment.”

Finn Santos of Freedom Print Lab & Nobody

More often than not however, finding the product that most fits the desired nostalgia of the customer takes more than sticking a wet finger in the air. Smash-hit Salcedo-based, Instagram brand turned restaurant Kodawari, achieved virality serving an anime, Japanese Pop-culture laced brand of dining. Toni Potenciano-Abesamis, freelance writer and creative director at Kodawari beckons that a brand extends far beyond just visuals–especially in the context of a product as physically gratifying as food. “The restaurant did become viral,” she says, “and this […] by the way, [was] not by intelligent design or anything on my end. I would say what keeps people coming back is definitely the food. It’s the happy mix of food, price and, in my opinion, how fast your food is going to come out.”

But how can you, sitting at your laptop, confirm that your business idea will find the same hungry public Kodawari is now serving? Frankly, in this fickle, capricious world, no level of googling or Chat GPT-ing will provide you that certainty.

Toni refers me to poet Richard Siken’s twitter page. “His advice was [to] read the stuff you like, but also read the stuff you don’t like. Because that’s the only way you’re going to know that your voice is needed or that your voice is valuable. So I guess it keeps me motivated just to consume.”

And while we were chatting about writing, this strikes at the importance of experience in forming your product. Where, in the mix of all your potential competition, will your voice, your product, be of the most value? It’s not the answer, but it’s a good question to start with. Because a sure fire way to create a business that takes off, and finds nowhere to land is by creating a product that nobody wants to use.

Abi Tan, proprietor behind 1C Coffee in Kapitolyo affirms that the best way to attract support to the business is by focusing on the customer. She says to “pull their needs and not push what you have.” Once you discover the core longings of a customer base you’ve found and have huddled around, staying on the discerned roadmap of servicing their wants is where the small business finds stability. “You will be easily tempted,” says Abi, “to go in another direction because of unforeseen circumstances that you stumble upon during the operations. Staying on the roadmap is one thing but discernment and business flexibility on the other hand may be necessary to recognize the need to change gears.”

Melvin Sun of BUILT Cycles, a business dedicated to strengthening the culture of bicycles and mobility, adds, “you have to be authentic and really intentional in strengthening relationships through participation or initiating gatherings and community building.” One community building exercise conducted by his team was EXPLORATOUR, “created in 2021 connecting our annual June 12 Kalayaan Ride to our July 11 anniversary as a platform to ride and explore new routes by bike, while supporting and fostering communities around small businesses and local brands.”

Toni Potenciano-Abesamis of Kodawari & And A Half

Attending to the Village

Given how young the business ecosystem in the country is, it has a vulnerability to it which builds a sense that entrepreneurs need to succeed together. To change legislation (on taxes for example) takes concerted effort. To create more noise for local businesses, often platforms (themselves businesses) have amplifier effects which allow small names and tight budgets to breach larger markets.

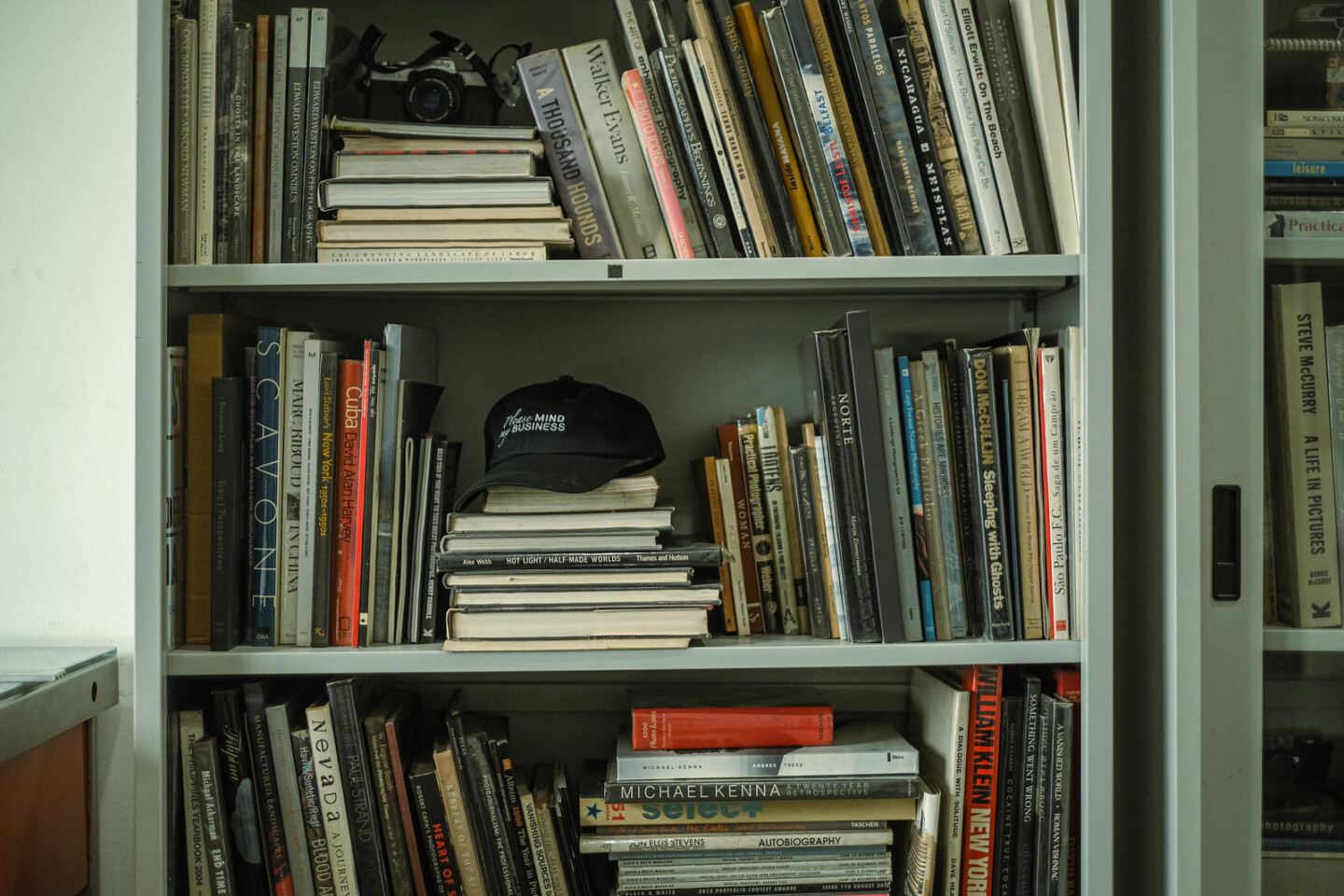

Jason Quibilan, himself a photographer, and founder of Shutterspace Studios which houses non-profit Foto Baryo and printing arm Silver, feels that more people are finally paying attention to work in photography. They’re finally buying works of art photography. What he notes too is the small village employed to have a work taken, printed, and treated for display. “Less than ten percent is the artist,” he says. “You have to work with your framers your printers, your curators, the people who have exhibitions, people organising submissions. So that’s one whole system. It’s not just artists and the art.”

Abi Tan of 1C Coffee

A great responsibility of attending to all the members within the village falls on the entrepreneur. It extends from the basics–of paying their employees properly, creating safe and comfortable working environments, and communicating the overall direction of the ship–and into functioning as a platform for everyone within the village–especially smaller players, to reach a greater share of the market, and in doing so create greater demand from customers.

Having been an ardent supporter of representation for such artists as Soika, Jan Sunday Paloma wields this responsibility as one of the country’s artist-run spaces. “[It’s a big thing] for spaces to be more compassionate and be more mindful of the artists’ welfare,” she says. “…The biggest factor that keeps us pushing forward is to see how much an artist has blossomed and grown through the space.”

Jason Quibilan of Shutterspace & Silver

Especially in creative industries, where the folks benefiting most from the available platforms are themselves artists, sustainability has been historically difficult to achieve. Jason Quibilan acknowledges this tension artists face. “If I am happy and secure in what I’ve done, whether it’s bought or not, or whether it’s appreciated or not,” he says, “I’m fine with that on one side, but on the other side—no. You have to do everything you can to make sure that you’re able to profit from that otherwise, the productivity is not complete.”

Jason apprehends the idea of the starving artist as a firmly romantic and dated idea. “Can’t you do what you want to be doing and be happy about it and still be rewarded for it,” he asks. And that comes with acknowledging that business owners are tasked with amply remunerating creators, and demanding the same from those that find them on whatever platforms they’ve created.

Entrepreneurs Create more than just Products

Joe Camacam, founder of Qubo, a haircut specialist for men and women now with two outlets in Manila, worked his way into business ownership with the epiphany that he was uniquely talented with a pair of scissors. Building on his passion, on the joy that happy customers gave him, Joe worked his way through junior to senior stylist roles–learning beard grooming along the way–to launch his now coveted shop.

Joe attributes so much of his drive to his family, but so too the individuals that have been with him on this journey. “I want to be different from mga owners ng businesses na pinasukan ko before,” he says. “I want to be different. Gusto ko mabigyan yung mga barbers ko ng mas magandang buhay.” Aside from creating opportunities for barbers, Qubo (literally meaning “home”) values more than just the product i.e. the haircuts. “It’s about building relationships,” he says. “[…] When I have first time clients, I always make friends with them. It’s not just haircut lang. It’s also about building friendship. That’s why I think […] that people [are] still supporting me.”

Joe Camacam of Qubo

In designing a business to be relationship focused and opportunity rich, entrepreneurs are making an existential decision. They’re binding themselves to a unique method of operations around which their lives begin to tangle. Restaurant ownership could very well mean long hours spent on foot; studio creation may mean managing large numbers of individuals, each with their own requirements; the list goes on. And it beckons the question to would-be entrepreneurs: is this the kind of life you’re hoping to lead?

It’s important to ask that at the onset–before you’ve hired people who suddenly intertwine themselves around your life, not just for mentorship but for sustenance. Before investors are on your capital table with their demands. Mark Zavalla of Saan Saan, soy candle and mindful implements workshop, left a career in the zippy world of tech to craft a life more closely attuned with his worldview.

Mark Zavalla of Saan Saan

“I always consider the brand or the business as something that supports me as an entrepreneur, something that I enjoy doing, something that’s not as stressful as an actual job,” says Mark. “I guess I’d want to make sure that I keep it as small as I can, but also, I feel that’s really the draw to the brand.” Pursuing what he calls “anti-growth”, having bootstrapped the business (which has its own web of difficulties), he has achieved a handle that some may find counterintuitive.

But, perhaps we’re beyond pursuing growth for growth’s sake. Entrepreneurs are using the buying power of the market to create objects, platforms, and services which nourish themselves–amidst the difficulties that come with operating. They’re orchestrating brands like shows where we, the customer, are blind to the travails behind the curtain. “[It’s] creatively solving [difficulties] without really telling the audience that,” says Finn of Nobody. And it’s never an easy process. “I think hard is temporary. It’s outweighed by the fun that we get from this.”

Melvin Sun of Built & Blocks

Mind their Businesses

So seek out local talent when possible. Nurse a tiring week with a weekend trip to a new restaurant, or a new coffeeshop, or a bazaar or fair. If the owner of the establishment is there, chat with them, ask them how they’re doing or what the inspiration for their brand is. If not that (because walking up to random folks with a to-ask list of questions is a lot to ask), try to nurture the latent curiosity within each of us that asks what our neighbour is doing.

There’s a real chance that someone within your proximity has a unique insight that they’re trying to share with the community. While asking the entire country to buy locally produced goods at all times may be too much–many of the decisions made regarding local produce are decided by government bodies rather than private ones–the excited curiosity to know local artists and what they’re working on is well within our grasp.

Mind your business if there’s a project you’re working on, and mind the businesses around you too. It’s not a solution, but it’s a mindset. And it’s a good place to start.

CREDITS

WRITER Jaymes Shrimski

EDITOR & PHOTOGRAPHER Marvin Conanan

SUPPORT PURVEYR

If you like this story and would love to read more like it, we hope you can support us for as low as ₱100. This will help us continue what we do and feature more stories of creative Filipinos. You can subscribe to the fund or send us a tip.